|

The next morning, we radioed Kodiak-Western Airways to order a new head for the Evenrude. We learned it needed to be shipped from Seattle and would not arrive for a week. So we organized our notes and posted maps and shipped rocks to Santa Cruz, and waited. Eight days later the head arrived on the afternoon mail plane and I installed it without incident. We finished a week of field work in the Shuyak region and picked up the stuff we stashed when I stripped the spark plug. Then we chartered a Goose back to Kodiak to prepare for our final excursion of the season: Puale Bay on the Alaska Peninsula.

Kodiak-Western Grumman Goose unloading gear at western-most Kodiak Island; Bill Connelly, Betsey, and Malcolm Hill. As luck would have it, we arrived in Kodiak the day of Smokey Stover's birthday celebration. Mr. Stover, like his father before him, had the nickname “Smokey” and owned the junkyard in Kodiak. WWII was good to the Stovers since the military left gobs of surplus steel on the Islands after the war, and much of it found its way to the junk yard. Smokey deserves a story of his own and I'll not go too far down that bunny trail. But it's necessary to write a few lines for you to appreciate him and others at the party. A bunny trail off a bunny trail is a bit like a dream during a dream: one loses track of the original thought after a while. But I've decided not to worry and just follow a stream of consciousness and enjoy the memories as they come. Be patient and we'll probably find our way back to the original story. We met Smokey a year earlier when we spent a week mapping the Raspberry Island area. He owned a fishing site at Onion Bay with two small cabins and he invited us to stay in the bunk house for the week. During our stay, we got to know Smokey and Doris, his Aleut wife. They were kind enough to share their secret recipe for clam chowder and we cooked it together one night in their cabin and I wrote the recipe in my field notebook (which I have to this day). This chowder was famous in the City of Kodiak since Smokey cooked it every Friday evening for anyone and everyone interested enough to drive to the junkyard and have a bowl. He dug the clams at Onion Bay and flew them back to Kodiak for all to enjoy. For years, he threatened to can the chowder commercially at one of the canneries during the off-season with his name and logo: “Onion Bay Clam Chowder: it lets you go in with the tide and wait 6 hours before pulling out”.

Smoky Stover settlement at Onion Bay, Raspberry Island.

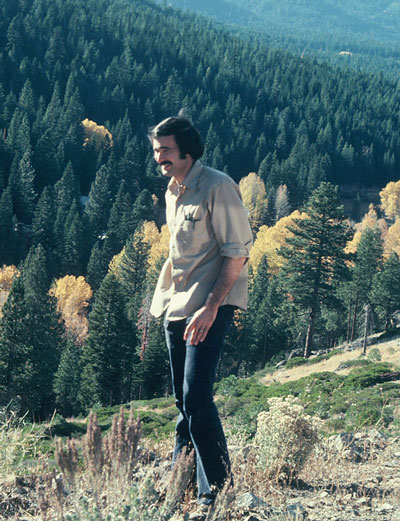

Unusual landforms on Kodiak; what would you name this one? The other thing about Smokey was his drinking. He bragged he was a “one-armed gill netter”. For those who never gill netted, it takes two strong arms to pull the gill net across the skiff and pluck the fish that are stuck by their gills. But Smokey, you see, always had a glass of scotch in one hand. When he flew to Onion Bay, he always came with two cases of Scotch for the week. At the end of my time at Onion Bay with Smokey, I saw for my first and only time what is meant by “DTs”. The weather turned bad and our chartered Goose was delayed three days. No Scotch: Smokey Stover was seriously ill. For those wanting to learn more about Smokey, I refer you to his own book written in 1976 and titled “The Retired Failure”, by Paul H. “Smokey” Stover. Smokey died a few years later and I met a man on a commercial flight from Alaska who attended his funeral in Kodiak. He told me it was the event of the decade and the wake lasted for days. Everyone was there. Kodiak is a tiny remote city, but fishermen and trappers and hunters from all over the Islands found their way to town by boat or seaplane to join in Smokey's party. Slim Truman and his wife and son TJ came from the far side of Islands for the occasion. Slim lives much of the winter in a modest cabin at a remote location on Hogg Island. I visited his cabin once when we were mapping that area and remember his reclining chair sitting next to a large picture window opening north toward to Shelikof Strait and the snowy peak of Saint Augustine volcano. His Hogg Island home site has two protected beaches, one facing east and one west, for safe skiff landing in most weather conditions. Slim owned seven gill net sites on the northwest side of Kodiak Islands and had lived in remote parts of the Islands for more than 30 years. Slim and TJ are the epitome of rugged Alaskan individualists. When Casey and I met TJ for the first time, it was his 21st birthday. TJ was raised in remote Kodiak waters and had only been to ‘town’ (Kodiak) four times in his life. Casey and I were mapping just outside Uganik Bay along the Shelikof when we first ran into TJ where he and two companions were fishing at their gill net site. We couldn't have been more different, yet the five of us ended up on the same distant beach that day. It was TJ's birthday and they invited us to join them at their ‘feast’ that evening. We were flattered, but at a loss since we had nothing to contribute. We lived on C-rations, clams, mussels, and any fish we could beg from fishermen. They said not to worry, since they had a side of deer on the fire and were fixing a wild strawberry and rhubarb pie. Casey and I rode our Zodiac five miles back inside Uganik Bay to our campsite, which was on a tiny beach backed against a steep sea cliff. We freshened up as best we could, gassed up the boat, and got ready to head back out to the feast. Casey was uncomfortable not having anything to contribute to the feast, but I told him with a wink and a grin, not to worry: I had it under control. It was 6PM when we returned to the gill-net site and the feast was nearly ready. I offered up a can of Coors to everyone and they were thrilled. The food was delicious, the companionship fun, the stories were beyond belief, and time passed quickly. The back drop was the snow covered volcanoes of the Alaska Peninsula across Shelikof Strait with waves breaking on the rocks below. How I wish to relive that evening. It was getting dark though and we had a five-mile skiff ride back to our camp inside the bay, so we began our salutations. I discretely slipped a Thai stick into TJ's hand as we stepped out of camp, expecting him to keep it for a special occasion. But alas, he rolled it up and lit it. What could be more special than now? After all, these were ‘now’ Alaskans. As Casey and I pushed off in the Zodiac, we were thankful for the full moon since twilight had passed into darkness. Ahh, but with the full moon comes very high tides, and with very high tides comes huge driftwood. The tides in the Kodiak-Shelikof region exceed 20 feet due to the swash effect and tonight the tides were at their highest. Huge driftwood and an inflatable skiff was a bad combination, especially at night. It was a slow and scary ride back to camp that night, and the Thai stick didn't help my navigational or boating skills a bit. When we finally arrived at camp, I tied the Zodiac to the running line I rigged up the day before. Slim showed me how to rig a running line at his gill net site several miles further inside the bay. It's like a cloths-line between buildings with pulleys and a looped rope. The landward end was attached to a boulder, and the seaward end was attached to an anchor with a crab-pot float above it. The idea was to tie onto the loop rope and run the skiff out to deeper water so when the tide drops, the skiff still is floating and therefore doesn't get damaged by waves on the rocks. Then when you need it, you pull it back in on the rope and untie it. Slim sat with me and had me tie the special knot several times to be sure I did it correctly. It's a bit like a hangman's noose in that it's a self-tightening knot. Knots came easy to me due to my training as a Boy Scout years before. Malcolm on the other hand, had no such skill and would tie the boat up with a spider web of rope. Since he didn't trust his knots to hold, he just tied more knots. So there I was, tired, a little loaded, and lashing onto the running line with an extreme high tide. We climbed into our sleeping bags on that sliver of beach next to the sea cliff, but there was little left of the beach with the high tide. Then the wind began to blow on-shore, raising the tide even further. Waves were breaking next to the tent and I was up many times that night dragging logs between the encroaching surf and our tent with no place to retreat. My skills with a running line were put to the test that night. “I hope the anchor holds.” “I hope my knot on the running line holds.” “I hope the skiff is there in the morning.”

Casey Moore in Superhot while tied to a running line. It was a long night, but with morning twilight I could see our Zodiac was just where we left it. Our coffee was scarcely hot when Slim Truman walked onto our beach from nowhere. We offered him coffee, and couldn't wait to hear the reason for his surprise visit and why he was on foot rather than in his skiff. He said he came to borrow our Zodiac since his oak skiff blew off his running line during the night. Wow, this was unbelievable. Slim and TJ are arguably the best skiffsmen in the Islands. How could it be that Slim's knot came loose and mine held? I rode with Slim and we went far inside Uganik Bay in the direction the wind had been blowing during the night, and we found his skiff undamaged. Before I leave Slim and this bunny trail, I have to share a short story he once told me. During the winter of ‘74, Slim was trapping along the Shelikof side of the Islands with a woman (not his wife) when their skiff capsized. It was winter cold and the woman died and he buried her as best he could. He was wet and had no supplies. He ate blue mussels off the rocks and ran on the beach to stay warm. A week passed before a boat came by and he flagged it down and was rescued. He probably was 70 years old at the time, but when he tells the story, it comes across with the seriousness of losing his way in the forest. And party they did. King crab, salmon, halibut, Onion Bay Clam Chowder, beer, and scotch. Liquor is an unfortunate part of Alaskan lifestyle. Too often it's the primary contributing factor to accidental deaths. We joined the party and it was especially fun since so many of the guests were people we'd met during our two years of mapping out on the Islands. We met these people in their cabins and boats where they shared their food, shelter, and colorful conversation. When the ocean was too rough for their rigid skiffs, they would see us out in our Zodiac and banging on rocks. At first they joked about us working from a “life raft”, but it wasn't long before we gained their respect. In the end, I'm sure we enjoyed them more than they enjoyed us. For all of us to be there at Smokey's party was special. We met these people individually in unlikely places. Sometimes it was nothing more than pulling alongside their boat and asking if they could spare a fish for a hungry geologist. In remote places like Kodiak, people are anxious for conversation. Almost always they invited you in out of the weather for coffee and a snack, and sent you away with salmon or halibut. Our time in the Islands was too short, and Smokey's party was the culmination. Those young blond geologists in the life raft everyone had been seeing and talking about were headed back to California for the last time. Well, after one more adventure at Puale Bay.

Shipwreck in the Kodiak Islands.

Puale Bay always held mystique for us. Before setting foot in Alaska, we read in Burke (1965) that the oldest known fossils from southwest Alaska come from a tiny islet near Puale Bay where Permian fusulinids are found in volcaniclastic arenites. Even though our research focused on the younger Mesozoic subduction complexes accreted seaward of the Alaska Peninsula, the relationship between these old fossils and our research area interested us. During our mapping at Kodiak, we found several localities with Permian fusulinids tectonically mixed into the Uyak Complex (Connelly, 1978). Casey managed to “bolt-on” a one-week excursion to Puale Bay as a finale to our Kodiak field studies to get a glimpse at that side of the arc-trench system. We silently accepted this as a boondoggle, but it was short, inexpensive, and pure geology.

Map of Kodiak Island and Alaska Peninsula showing Puale Bay. We stripped our gear down to bare necessities for the three of us and loaded everything in a Goose at Kodiak-Western Airways. We arranged for a return charter flight a week later, but had enough food for 10 days. Landing on Puale Bay was dicey, but we set it down on the third attempt. The Pacific swell was large and the Goose was heavy with equipment. We taxied to shore and unloaded the Zodiac, outboard, food, radio, and other supplies. Then we took note of signs of grizzly bears in the area. There were no trees in the region, but the grass, fern, and iris were lush. The sea-cliff was about 20-feet high and along its rim there was a three-foot-wide well-traveled bear trail as far as we could see. We jokingly called this Grizzly Express since it obviously was heavily traveled. There was a tiny deserted log cabin on the sea cliff, which was in-part dug into the tundra. It was constructed from drift logs from the beach below. Its door and window were lost sometime during its many years of exposure on the cliff, but the roof appeared relatively intact. Grizzly Express passed just in front of the cabin and a spur trail went into the cabin door.

Preparing cabin at Puale Bay, Malcolm Hill and Casey Moore.

The three of us stood there silently examining the cabin and considering our shelter options while remembering our various encounters with grizzlies and experiences with foul weather; and weighing which would be the better of two evils. Our memory of the time our tents almost blew away during a heavy rain storm at the mouth of Uyak Bay during our first night in Alaska was indelible. The tundra was so thick the tent stakes were worthless. We brought boulders from the shore and piled mounds on every stake, then put more boulders inside the tents for ballast. We seriously wondered if this Alaska field research was going to work, and if we were going to make it through the night. We wondered where our skiffs would be in the morning. Since then, we always tried to find an abandoned cabin, however dilapidated, to use for shelter. I recall one cabin on Ban Island that was so bad we put our tent up inside the cabin, nailing the tent to the floor. The roof was virtually gone, but there were walls to which we could hang our Helly Hansens, and a floor to keep us out of the mud. Yes, we all agreed any cabin was better than no cabin, bears or not. We moved the gear up from the beach, loaded our pistols and rifles, laid out our sleeping bags, and discussed the bears.

Cabin located at western-most Kodiak Island at Halibut Bay; note latrine in foreground; Betsey Hill, Casey Moore, Malcolm Hill, and Bill Connelly.

Cabin located in northern Kodiak Islands.

Not long before that year's field season, we all had seen the movie “Never Cry Wolf”, about a loner zoologist who studied wolves in northern Alaska. We recalled his turf battle with a particular wolf and how he drank copious amounts of tea, then ‘marked’ his territory in a manner the wolf would understand and respect. We talked about our situation with the grizzlies and felt a similar strategy made good sense and agreed to proceed accordingly. We broke out a case of Coors and began ‘marking’ our territory: Casey went north, Malcolm went east, and I went west. During our week at Puale Bay, we had no encounters with bear at the cabin.

Cape Kelkurnoi at Puale Bay, Alaska Peninsula.

Nevertheless, I slept with my 41-magnum pistol under my pillow, and the 30-06 rifle rested at Malcolm's side. Casey was of the school “walk loudly and carry no stick”, and never carried a gun. Instead, he fastened a brass bear-bell on his pack so as not to inadvertently surprise a bear. I found the constant dinging annoying and argued he was depriving himself of all wildlife, not just the bears. But the bell seemed to work and he never had an encounter. Speaking grizzly deterrents, I'm reminded of a bear coming into camp once in the northern Kodiak Islands. I fired the 30-06 over its head to detour him, but the report only increased his resolve. After a second, then third shot, I was seriously considering killing him since he was getting dangerously close. Instead, I grabbed a frying pan and beat on it with a rock pick. This clanging of metal against metal terrified the bear and he fled immediately. This supported Casey's theory of a bear-bell. Our goal at Puale Bay was to study the dozens of tiny islets within a couple miles of shore. Early the next morning, we inflated the Zodiac and prepared it for the rough seas. We could not land the Zodiac on the islets without damaging it since the swells were too large and the rocks too jagged for a rubber skiff. So one of us drove the skiff in close enough to drop the other two off, then quickly retreated to deeper water. When the two geologists completed their studies of the islet, the maneuver was repeated to pick them up, and we moved on to the next islet. This system was working well and we systematically mapped a dozen or so islets over four days. We mapped interesting anticlinal structures, a large fault, and found the Permian fusulinids. On the fifth day, Malcolm was driving and dropped Casey and me off on an islet and we were beginning our usual studies. Malcolm retreated to deeper water and turned off the motor and was peacefully reading a paperback while he waited for us to complete our work. As Casey and I hiked over to the opposite side of the islet, we saw a small island in the distance with a sea lion rookery. This was interesting to us as we had never seen one before. We'd seen seal rookeries several times on the Kodiak Islands, but never sea lions. As we stood there admiring it, a large group of sea lions jumped into the water and began swimming in our direction. When they got close to our islet, they split into two groups and went around both sides of the islet. This seemed to happen quickly and it wasn't clear yet what was going on. There was lots of white water due to the way they were swimming shoulder to shoulder and they all appeared to be large bull sea lions. In what seemed an instant, the two groups came back together on opposite sides of our Zodiac where Malcolm continued to peacefully read, ambivalent to any of this sea lion drama. His first awareness was when they started bearing their teeth and growling just a few feet from the skiff and on both sides! I'll have to be honest, Casey and I were rolling on the ground we were laughing so hard. Malcolm was trying with all his might to start the outboard and flee, but it would not start. I suspect he didn't remember to flip the switch to the ‘on’ position in his haste. In the end, the bulls were there to intimidate, not to harm. Malcolm finally started the outboard and fled and no harm was done.

Sea lion rookery near Puale Bay. The only other time we had an intimidating encounter with a marine mammal was back in Uganik Bay. It was early in the morning and we were boating northwest toward the head of the bay where we were going to map. I was driving that morning and Casey was with me. The Zodiac was on a plane and we were at top speed of about 22 mph as the motor roared. It was a 45-minute ride to the mapping area and our minds were drifting as we sped along. Out of nowhere, an enormous Orca whale broke water from the rear starboard side of the skiff and about half its body came out of the water before it dove under the bow, splashing water on both of us. The Zodiac was 15-feet long and this killer whale was considerably longer than our skiff. It was stark black and white and it had a large dorsal fin. No sooner than this monster dove under the bow, then another Orca came from the rear port side of the skiff and repeated the same maneuver and dove under the bow. Casey's eyes were the size of half dollars, and I suppose mine were the same. What to do? We were going full speed already, so out running them wasn't possible. We were at least a quarter mile from shore. I had my pistol on my belt, but shooting a pistol at these monsters seemed silly. Casey just shrugged his shoulders since conversation was difficult with the noise from the outboard. The Orcas made two more of these bow dive maneuvers, then disappeared. In hind sight, it seemed to us they were just playing. Our week at Puale Bay came to an end too soon, but our goals were accomplished. Kodiak-Western sent a Goose on schedule to pick us up, but sadly the sea was too rough to land and it flew back to Kodiak. So we waited. The next morning, we heard the Goose coming, make a couple passes in the clouds, then flew back to Kodiak. Again we waited. The third day brought more disappointment and these geologists were getting edgy and food was getting low. The fourth day was the charm. I have a cherished black-and-white photo of Casey standing on a gravel beach berm with the Goose flying low behind him as it approached to land on the bay. This was my last adventure with Casey or Malcolm, though each of us separately have had many adventures since.

Casey Moore waiting for Goose to land and pick us up at Puale Bay 4 days late after bad weather.

It was 8:30 in the morning when I awoke to the sound of a dart game between a couple bearded geology students who were drinking coffee and rambling on about the incoming Freshman class. I was sleeping on the old couch I'd owned for years and had moved many times between rental houses. Now it was parked in Office 117, which was my lab at the University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) since I hadn't found a place to live yet for the semester. Finding housing for fall semester was highly competitive and only the fast and unscrupulous students enjoyed early success. I generally did well, but we were delayed returning to Santa Cruz from Kodiak and housing was picked over by the time we arrived. Classes were in session, but as a fourth-year grad student, I wasn't taking any formal classes. Instead, I was taking Independent Study to work on my thesis and a Research Associateship to earn some money. My VA benefits from my time in Vietnam had run out before I entered grad school, so TA’s and RA’s were my sole source of income. I'd passed my Ph.D. Candidacy Orals the prior spring and completed my field research over the summer, so now the only things between me and my Ph.D. were analytical work and typing.

Jerry Weber on my couch in Office 117. Graduate students were quick to get back into their study routines once summer ended. Days were long and intense, but since everyone was working with similar intensity, it seemed normal and was a bit like being monks in a monastery. Budgets were lean, but tastes were simple. Excitement came largely from academic breakthroughs of our own or of our colleagues. The camaraderie was indescribable. There wasn't much time for anything that wasn't academic, so domestic chores like grocery shopping were low on the priority list. One of my colleagues was known for going to Safeway and rather than taking time to push his own shopping cart through the market, would find a suitable unguarded cart and highjack it. My closest companion during my four years of grad school was Beau, my Australian Sheppard. Beau attended most classes with me and was something of a department mascot. He ran free and greeted people at will. Though small in enrollment, UCSC was an aerially large and relatively undeveloped campus located in a redwood forest along the northern California coast. In the 70’s, it was a young and very liberal campus. There were no rules about dogs on leashes or dogs in classrooms. My hair was long and wardrobe consisted tasteless cloths such as cutoff jeans, t-shirts, and beach-walkers. When I wasn't in class or my office, I was at the beach SCUBA diving or surfing, or running with Beau in the forest. A number of grad students were “career students” who were in no hurry to leave Santa Cruz and join the ranks of working America. After all, this was the land of 'sun, surf, sand, sex, and dope'. Why would anyone in their right mind give this up and go to work? I was different. Coming from humble origins and living on pittance, I was anxious to graduate, get a job, and have an income. I was going on 29 and hoping to graduate before turning 30. It would be a Geology Department record to earn a doctorate in four years, but it seemed achievable. My field work was finished and Candidacy Orals passed; now all I had to do was write my thesis, and bam, it'd be done. I worked many late nights and was voted by my peers the most likely student to be working past midnight. My old mechanical Corona typewriter could be heard pecking away hour after hour, night after night. When one draft was finished and edited, retyping began. In the end, my thesis was accepted before I turned 30; and under four years. It’s my understanding this remains a department record. There were enough diversions along the way to keep us from burning out. Sandy was particularly amusing when he would tap on the lab window as he walked along the outside walkway and yell through the glass with a shit-eatin’ grin, “Hey Bill, there's a train wreck in the forest”. He would make the rounds and usually manage to find one or two students to join him and the banana slugs in the forest for a joint before calling it a night. Or there were the late night runs to town to the Crow's Nest or Mona's Guerilla Lounge or Fast Eddie's. I recall several times when we'd be sitting in class and someone would walk in and discreetly say “surfs up”, and a handful of us would slip out to go surfing. The surf wasn't up often, so it was an event we didn't want to miss.

Sandy Horan (right) in the forest behind Applied Sciences. As the months clicked by, my thesis was nearing completion. In late 1975, Casey suggested I interview with AMOCO Production who would be interviewing in the department two weeks hence. I had no interest working for an oil company, but obliged Casey (my advisor) since the interviewer was a geology alumnus (Dave Work). The two weeks came and went and I forgot about the interview. I had just returned from running in the forest at lunchtime and when I came into the lab Casey asked what I was doing there. I look puzzled and answered, “I work here”. He reminded me I was supposed to have been interviewing with AMOCO 15 minutes ago. I quickly headed to the interview in my usual garb: cutoffs, t-shirt, bare feet, and sweaty. The interview went well and they offered me a job. Naturally, it was contingent on completing my thesis and receiving a Ph.D.

Casey Moore with his baby girl, but still writing professional papers in Office 117. In the spring of 1976, the final writing of my thesis was underway. AMOCO asked me to join their Field Party for seven weeks mapping the Tertiary strata on the southeast side of the Kodiak Islands. I accepted since I needed a break. Compared to my graduate excursions with the Zodiac, it was a lackluster trip, but was it fun to work with helicopter support for the first time (even if it was an old Hiller helicopter).

Bill Connelly with Hiller helicopter on Kodiak Island with AMOCO project.

When I returned to UCSC, I was reading a 1943 USGS Bulletin about the Sitka Greywacke on Chichagof and Baranof Islands in Southeastern Alaska and felt from the descriptions there may be blueschists mixed in with these greywackes. Blueschists are important metamorphic rocks since they contain the minerals glaucophane and crossite that form during high-pressure, low-temperature metamorphism deep in subduction zones. In 1943, the significance of these unusual sodic amphiboles wasn't recognized, so their presence often was overlooked. We already found a first-occurrence of blueschist in Kodiak and published it (Carden, Connelly, and other, 1978), but the thought of possibly another blueschist first-occurrence in Southeastern Alaska was exciting. I called John Carden at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks and told him of this 1943 article and my thoughts, and he shared my enthusiasm.

Map of Chichagof and Baranof Islands. We put in at Sitka which is located inside Sitka Sound, and worked our way northwest across Khaz Strait to the inland waterways of Baranof Island where we were picked up by a Beaver 10 days later. Casey was on vacation, as was John's Advisor (Bob Forbes), so we worked up a plan for a quick field excursion to the region in hopes to making a discovery. John said he could come up with enough money from his grant to buy airline tickets for both of us to fly to Sitka if I could come up with a Zodiac, outboard, and related field gear. Time was short since it was late in the summer, so we planned to rendezvous in Sitka two weeks later. Upon arrival in Sitka, we went to a local outfitter and arranged for a Beaver float plane to pick us up from a location on north Chichagof Island nine days hence. We bought food and supplies, enough gas to make the one-way trip north, blew up the Zodiac, and off we went. John had little experience with skiffs, but I was experienced from two field seasons on Kodiak. Our route was primarily along inside passages where we were protected from rough Pacific swells, and there were few bears. We collected many metamorphic rocks along the way hoping some of them would contain the critical mineral assemblage with glaucophane or crossite. We could not know for sure if we found the correct assemblage until we returned to our universities and cut thin-sections of the rocks and examined them with polarizing microscopes, so for now all we could do was use our hand lenses and hope.

John Carden in Zodiac, Pinta Bay, Chichagof Island.

The weather was very rainy and we wore our Helly Hansen rain gear and sau’westers every day. The countryside was spectacular and heavily forested with Sitka Spruce with undergrowth of fern, iris, devil's club, salmon berry, and grass. Many of the small waterways were brackish and full of star fish of all colors. Only rarely did we see anyone along the way since fishing season was over. When we reached the north end of the inland waterways of Baranof Island, we had to cross Khaz Strait to get to Chichagof Island. This was the most dangerous part of our journey since we had to traverse open Pacific Ocean. The Zodiac was heavy with supplies, gas, and rocks, and the Pacific swells were large. As we approached Chichagof, we were looking for a tiny opening called Skiff Passage which was the access to the inland waterways of Chichagof Island. However from the low vantage of the Zodiac, all we could see was white water from the waves breaking on the rocks. There were rock reefs all around us and as the swells lifted and dropped us, jagged rocks disappeared and reappeared from the sea. A single mistake here would be a disaster. I was driving and John was spotting rocks and trying to locate the Passage from the map. But all we could see was white water and nothing looked like a gap in the white water that would be the Passage. So we inched closer and closer to shore with ever more rocks and roaring white water. I was seasoned with skiffs and Alaska and all, but I'd reached by pucker-point and said to John “this has me really nervous!” John calmly answered “don't worry Bill, people don't die easily.” We kept picking our way through the reefs and miraculously found Skiff Passage.

Slocum Arm, Chichagof Island.

Along the way, we came across a couple deserted gold mines and stopped to explore them. At one of them, John noticed a 55-gallon gasoline drum that still had a few gallons of gas in it. We emptied three gallons of gas from it into one of our empty outboard cans and went on our way. When we finally reached our destination, we had one extra gallon of gas! The Beaver picked us up four days late due to bad weather. We split the rock samples in two and each of us took our split to our lab to analyze them for blueschist minerals. In the end, all of John's samples were barren and I found blueschist minerals in only one of mine. This single blueschist sample sits proudly on my bookshelf today, but I'm the only one who knows the story behind it. The trip was successful and we published our blueschist first-occurrence article within months.

This is the sole confirmed sample of blueschist from the Baranof-Chichagof expedition, and contains abundant crossite (a sodic blue amphibole). Photo taken on the bookshelf in my office. A professional typist had been finishing the 'final' version of my thesis during our boondoggle to Southeastern Alaska and now it needed my editing. Everything seemed to be coming together perfectly until I read a newly published article by George Moore from the USGS about the Uyak Complex. In it, he described some new Upper Cretaceous radiolarian fossils he extracted from red chert collected at Uyak Bay on Kodiak. This was a bombshell with regard to my interpretation of the age of emplacement of the Uyak Complex, the topic of my thesis. We'd collected many fossils from the Uyak area and they ranged from Permian fusulinids to Lower Cretaceous radiolaria, but nothing this young. We interpreted the age of accretion of the Uyak as Triassic to Early Cretaceous, so these new Upper Cretaceous fossils were inconsistent with the interpretation imbedded in the thesis I just typed and was about to turn in. I was suspicious of these young ages. During our fieldwork, we collected many radiolarian cherts and sent the samples to Pessagno at Rice University for age dating. Pessagno was the only micro-paleontologist who sorted out the Cretaceous radiolarian biostratigraphy, so we needed his help. Unfortunately, Pessagno lost our samples and never did any dating of them. Moore was a friend and colleague of two other USGS Alaskan geologists (who shall remain anonymous) who got crosswise with me a few months earlier and sent a scathing letter to Casey (my Advisor) suggesting I was about to “scoop [publish] some of their ideas” based on discussions I had with them at their USGS office in Menlo Park. This was nonsense and Casey knew it since the ideas I was being accused of stealing had been discussed numerous times between Casey and me before my visits to Menlo Park. It was highly irregular for seasoned USGS geologists to accuse a grad student in this manner and Casey set them straight. I never trusted any of them since then, and suspected foul play about the new radiolarian dates since all of these USGS geologists were friends of Pessagno. Moore's young samples allegedly came from an outcrop at the west head of Uyak Bay; an outcrop we had collected in 1974 and sent samples to Pessagno. Before I was going to re-write my thesis, I wanted to be certain these radiolaria were really from Uyak, and really Upper Cretaceous. I withdrew the last of my meager savings from the bank and bought an airplane ticket to Kodiak, alone. Then I caught the mail plane from Kodiak to the Larson Bay Cannery. I managed to catch a ride on a fishing boat out to the mouth of Uyak Bay where the radiolarian cherts outcropped, and recollected several good samples. Getting back proved more of a challenge. Working alone in bear country isn't advised and it was a long hike back to the cannery. After hiking 15 miles, I came on a young couple working a tiny subsistence farm on the coast and I stayed with them for a few days. They offered me a ride to the cannery in their boat, but they wouldn't be leaving “right away”. The departure date kept slipping as they enjoyed an extra strong back to help with their heavy work. When I returned to UCSC, I extracted the radiolaria from the chert with hydrofluoric acid and bought a ticket to Texas to visit Pessagno. I wanted to retain custody to the fossils and see with my own eyes these particular radiolaria were Upper Cretaceous.Well, they were. I went back to UCSC and began re-writing my thesis. My RA had run out and I had no savings and no source of income. AMOCO’s job offer remained good, but I needed to finish my thesis before I could begin work. I was completely broke so I moved out of my rental house and into a tent in the forest. Thank goodness for all my Alaska field equipment. I knew the forest well from running there and found a ring of redwoods deep in the forest and put up my tent in the middle. It was far from any trail or road and each time I walked to it I approached from a different route so as not to beat a trail. I had my guitar and a few personal things in the tent and I didn't want anyone finding the camp site and stealing stuff. Beau and I enjoyed living there except when the coyotes would wake us. I had a small camp stove there, but did most of my cooking on a hot-plate back in my lab. I showered either in the thin-section lab in the basement or at the field house when I went swimming. It was a novel existence and I rather enjoyed it for the three months we lived there. I never showed anyone where the tent was located, but I once described its location to Dan DeCristoforo. DeCristoforo was mapping the metamorphic rocks on campus for his Master's thesis and knew the forest well.

Dan DeCristoforo mapping in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

A great side story named Bagby's Orals was written by Dan DeCristoforo in 1989 with the intention of publishing, but it wasn't accepted. Babgy’s Orals describes events following when Bill Bagby failed his Ph.D. Candidacy Orals in early October, 1976. Before the night of his failure ended, DeCristoforo, Bagby, Vaughn, Sandy, and Allwardt staggered through the dark to find my tent in the forest based on DeCristoforo’s drunken recollection of where I told him it was located. Maybe someday he'll have his story published or let me include my version of his story herein. By the end of October 1976, my thesis was complete and it was time to pack my meager possessions and move to Denver to begin my career with AMOCO. But alas, my cherished rock collection was not going to fit into my 1967 VW bug. I'd collected countless rocks during my years as a geology student and they could not be left in the cabinets in my lab. Most of these rocks didn't look like anything special, even to a fellow geologist. But to me, every one was special and unique and could not be left behind. I toiled with this for several days until an epiphany came to me. The next morning, I took them out in the forest next to the Applied Science Building and carefully stacked them in a neat three-foot high conical pile at the foot of a proud redwood tree. I nailed a placard on the tree above my abandoned rock collection that read, “Connelly Memorial Rock Garden (under construction)”. Years later when I returned to visit, my rock pile had grown and now was enormous.

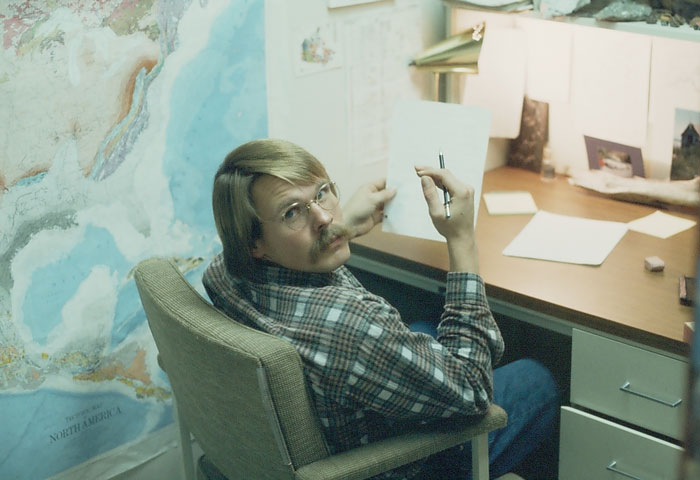

Bill Connelly finishing thesis in office 117, UCSC, 1976. Go to Chapters 5 & 6

|