|

“Well, how's your credit son?” “I actually don't have any credit ma'am, but I'm a geologist for AMOCO downtown and I have a Ph.D.” “Do you have any local rental references?” “No ma'am. I just moved here from California two weeks ago; but I'm a good tenant and will keep your house clean and pay rent on time. I've never made a late a payment in my life.” “You look like you're a bachelor and I've had bad luck renting to bachelors.” “No Mrs. Jenson, my wife's still in Santa Cruz while I find a house for us here in Denver. She'll come out as soon as I find something.” “Do you have any kids?” “No ma'am; just my dog Beau, and he's very well trained and rarely barks. I really like this old house because of the open fields and dirt roads where I can run. Do your kids go over there in the fields often to play?” “They do. There's a canal back there and asparagus grows along it in the spring.” … Then there were two minutes of deafening silence…. “Well son, I don't usually rent without references, but I have a good feeling about you. When did you say your wife will be moving out here?” “As soon she quits her job and puts things in order. Thank you very much and you won't be sorry. How much shall I make this checkout for?” Thus began my tenure at 4820 McIntyre, Golden, Colorado, with Kathy Jensen. I figured once she got to know me, she'd forgive me for the white lie about my wife, or lack of wife. I rented the old house in November, 1976, and it was Christmas Eve when I went next door and stood on her doorstep with my tail between my legs intending finally to come clean. I rang her doorbell and stood there in the dark and snow waiting for the door to open. When finally it opened, Kathy stood there with a pleasant but apprehensive smile on her face. I said to her meekly, “Kathy, I have something I need to tell you”. She interrupted, “I know Bill, you're a bachelor”. By then I'd gotten to know her and the kids well and spent lots of time with her son Doug playing in the fields. Kathy realized I was a good tenant, even though I wasn't married. She gigged me about my white lie for many years later, even after her two daughters helped raise my three daughters. Fact was I hadn't been married since the spring of 1973 when Marcia moved out while I was hiking in Havasupai Canyon during spring break in my first year of graduate school. We'd been married since 1970 and had met years earlier while working at Camp Loch Leven in the San Bernardino Mountains. We traveled, hiked, and camped a lot and enjoyed a simple life on a meager budget. It was never clear why she left, but she never looked back. I believe it had a lot to do with my over commitment to studies. The divorce was simple and fast since there were no children or assets. Divorce came to most grad students and professors during my time at UCSC. I was jolted and came close to dropping out of grad school. It was a comment from my older brother Bobby that swayed me enough to continue my quest for a doctorate. “Billy”, he said, “you know I can't ever do anything like that, so please do it for me”. Bobby suffered from brain damage from a fall when he was three years old and remained challenged for life. He was robbed of his true potential. Alexander, Bobby's only son, is a genius and just completed medical school. He's living proof of Bobby's genetic make-up. This is another story that needs to be told and I'll get to it later. Born in Hollywood and raised in southern California, snow and cold were new to me. My first paycheck from AMOCO was spent on a down expedition parka at Hallubar since I had only light California clothing in my wardrobe. Adorned in my new parka, I accompanied some other young geologists from AMOCO skiing on several trips during the winter of 1977. The exhilaration and speed of downhill skiing appealed to me, but I was a classic case of ‘more balls than brains’. In March, I was skiing at Loveland Basin when I suffered a major spiral fracture in my right tibia and ended up with a cast up to my crotch. I'd been on crutches with broken legs twice before and was quite mobile with them. But working downtown Denver with snow and ice on the ground presented new problems. The biggest challenge was driving my VW bug, which naturally had a standard transmission. After some thought, I devised a method whereby I hung my right leg with its cast over the passenger seat. With my right hand, I used a three-foot-long stick to push the throttle peddle, and used my left foot for the clutch and break; while steering with my left hand. Starting off on an uphill slope was most difficult. There, I would use the hand break with my right hand and throttle with my left hand to initiate forward motion. Once moving, I could steer with my left hand and throttle with my right. Thank goodness I was never stopped by a patrolman.

Bill's VW brought to Colorado from Santa Cruz; the "wax me" was compliments of DeCristoforo Summer was arriving soon and I was to be Party Chief for AMOCO on the Alaska Peninsula in July with three geologists and a helicopter. Knowing how demanding field work was, I needed to be in top physical condition, and here I was on crutches. I discussed my predicament with the orthopedic surgeon (Dr. Waller) and he put me on an aggressive rehab schedule. He replaced the full-length cast with a very tight knee cast after only two months so that I could start regaining my knee flexibility. He put me on physical therapy at that point to begin strengthening, but I could feel clicking between the broken bones and it was spooky. He said not to worry because this micro movement between bones caused the bones to grow faster, so long as I could tolerate the pain. I've always had a high tolerance to pain, so the therapy continued. After three months, I graduated to a walking cast and used a fine old knobby wood cane I inherited from my Grandpa Connelly. I rather enjoyed my new persona at work where I wore a three-piece suit with a fancy gold pocket watch and used my cane as a pointer during presentations. The cast was removed only three weeks before my departure to Alaska and I rode my bike daily to loosen my joints.

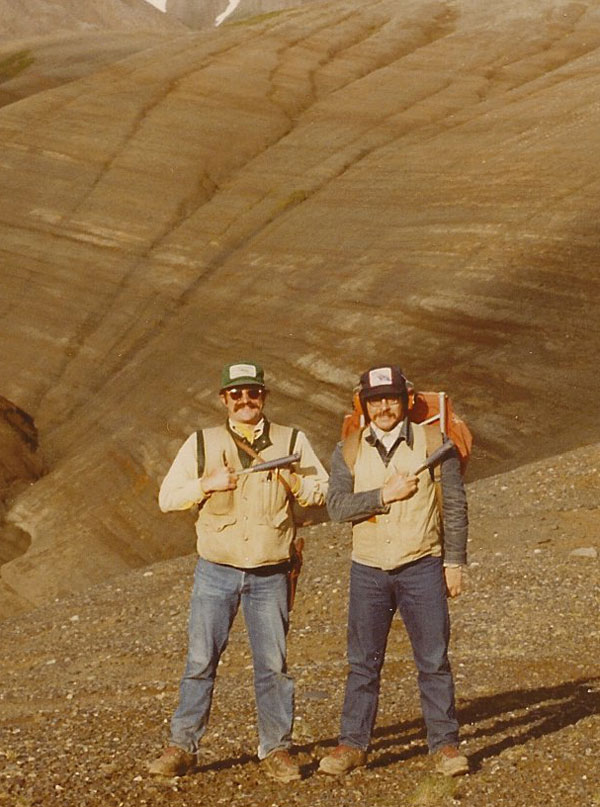

Leonid Smirnoff and I first met in George Simmon’s office in May 1977, two months before we were to join the Alaska field party. George was my immediate boss at AMOCO and was commonly known as “Bulldozer” by those who worked around him enough to appreciate his style. I related to George and always knew how things stood between us, though would have preferred a different ‘handle’ than “big balls”. He gave me one bit of advice early on that I've shared with several other young, hotheaded prima donnas along the way. He told me there are some days the best thing he could do (and by suggestion, I could do) is go home early so as to avoid causing too much damage due to his temperament. Leonid had just immigrated to America from the Soviet Union as a political refugee and AMOCO was his sponsor. He had a Ph.D. in Geology from the Leningrad Mining Institute and several years’ experience mapping in the Urals. He fell from favor with the Soviet government when he declined their invitation to join the Communist Party. He told them, “I'm a very busy man and I know I'd forget to attend your meetings”. Within a couple months, his job was changed from a prominent geologist to a coal stoker. This is a brief overview of Leonid Smirnoff and I will tell more of his fascinating story in the pages that follow. But this day I learned Lee was to be a member of my Alaska field party. Lee obviously was quite fit and I later learned he once was an Olympic swimmer. His English was poor, but his credentials were excellent. We ended up working together in the field for two seasons, and in the office for two years. We became good friends and worked well together, though we often had heated arguments about geology. We even co-authored a professional paper in Geology Magazine about some petrified forests we discovered on the Alaska Peninsula (Smirnoff and Connelly, 1980, Axes of elongation of petrified stumps in growth position as possible indicators of paleosouth, Alaska Peninsula).

Leonid Smirnoff next to petrified Sequoia stump in growth position, Alaska Peninsula

(I took many pictures in Alaska and Lee loved having his taken. In 2009 I scanned many pictures of Lee and posted them on a website for his children to enjoy since they did not have the pleasure of knowing him during his prime. The reader is invited to go to the website and see Lee and many of the places I discuss in the following pages: Smirnoff).

Alaskan summer days are long and we worked diligently, typically starting at 6AM and finishing at 7PM. We chartered a helicopter for the summer at a considerable expense ($93,000 in 1977 and $76,000 in 1978) and felt compelled to keep it busy. We worked primarily along both sides of the Alaska Peninsula, the Kodiak Islands, Lower Cook Inlet, and the Bristol Bay and Dillingham areas. We almost always were near the ocean, volcanoes, bear, and salmon. Our focus was measuring thousands of feet of stratigraphic section, describing it in detail, and systematically collecting rock samples. All work had to be carefully documented and ultimately put into reports where they live today in AMOCO’s vault (now BP). The purpose was to understand the surface geology so as to predict the subsurface geology under Bristol Bay and Lower Cook Inlet so when those areas were leased for oil and gas exploration, AMOCO could bid competitively.

Generally, there were three geologists in the field party plus a helicopter pilot and mechanic. We stayed in remote quarters as available near our changing field areas. We flew endless hours back and forth over the Aleutian Mountains, Bristol Bay Lowlands, and coastal waters every day, and saw countless grizzlies, caribou, moose, wolf, sea otters, fox, whales, sea lions, eagles, and more. There was so much to see; every day, all day long. The weather often was difficult and we dressed accordingly. There were grizzly bears everywhere. Steve Papajohn was my field assistant and his sole job description was to stay close to me and carry a 458-magnum carbine. Lee and I both carried a 44 magnum pistols on our field belts along with our Brunton compasses, rock hammers, and notebooks. We were chased by bear twice and had other close encounters. From the air, the bear didn't seem threatening, but from the ground, they are up to 13-feet high, weighed as much as 1300 pounds, and ran quite fast. Guns were as much a part of our field gear as rock hammers.

We pretended to be on a quota and forced ourselves to measure a certain number of feet of section every week, rain or shine. This often put us in dicey situations as we pushed ourselves beyond our limits. I recall glaciating high across a steep snow bank on the Alaska Peninsula with Greg Brown, Steve, and Lee, and wondering what the hell we thought we were doing up there. Greg was an excellent rock climber and we had to be sure never to let him take the lead less he put us in harm's way. He was an F4 pilot during the Vietnam war and had nerves of steel. We screwed up this day and Greg led us across this very scary steep ice face and we were digging holes for our feet with our rock picks. We never had ropes or proper gear for this sort of thing. We were several hundred feet above the valley floor and measuring a prograding deltaic sequence. Lee missed a foothold and slid all the way to bottom, speeding up as he went. There were a few two to three foot boulders near the base of the ice sheet and he banged into a couple of them with his legs as he slid by. His legs were seriously bruised, but not broken, and there were no blows to his head.

Lee and I were measuring section one day along a steep knife-edge ridge composed of silty claystone. The strata were poorly consolidated and supported no vegetation. It was windy with light rain, so the clay-rich rocks were very slippery. We were making good progress as we measured section from the top of the ridge downward. I saw a good spot to measure a bedding attitude on the side of the ridge and jumped onto a minor ledge. I misjudged the surface and slipped over the side. I'd slid about 12 feet down before managing to catch a tiny edge with my left boot, and another edge with the finger nails on my right hand. I was suspended there a thousand feet above the valley floor hanging by a hope and a crack trying with all my intellect to figure a way back to the top of the ridge without slipping to my death. Then Lee starting carrying on like a magpie. “Beel, one step death! Beel, one step death!” Russians have trouble with their “i” and they always sound like “ee”. “Beel!”, he kept shouting. Finally I shouted back,” Lee, will you shut up and throw me a rope!” Well, we didn't have a rope. He dug through his pack and found a short length of quarter inch nylon cord and somehow we managed to get me back up on the ridge with no injuries. To this day, I've never gotten over my fear of heights.

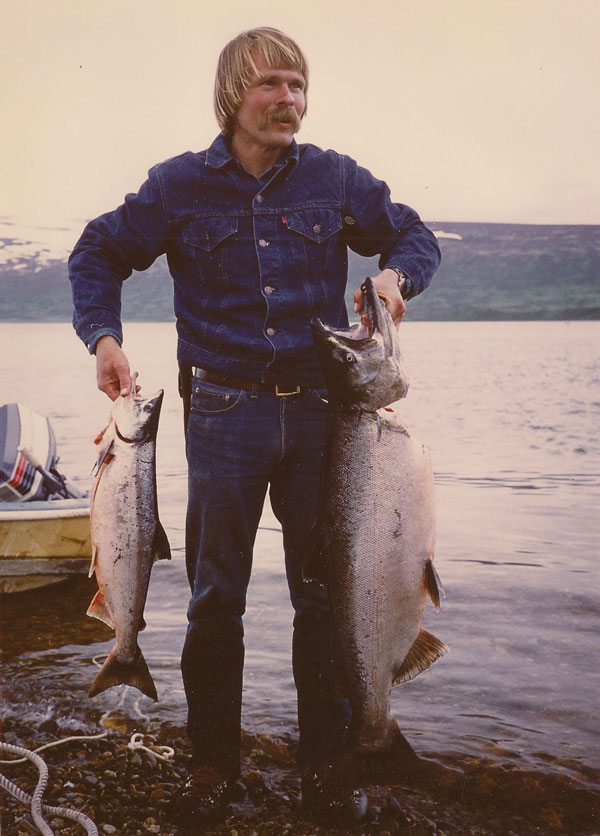

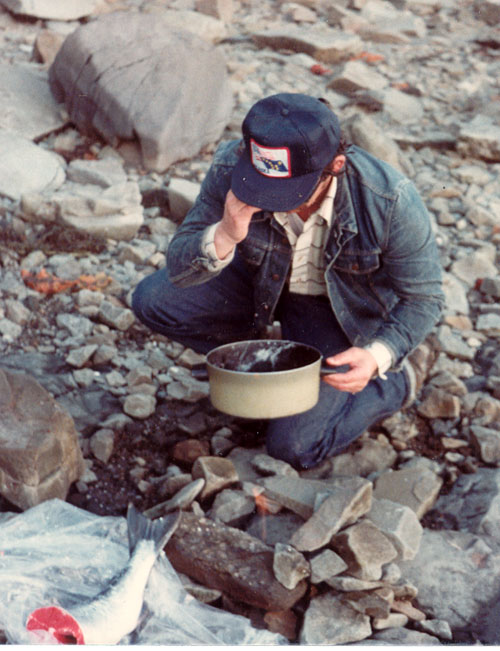

Near Port Moller on the Bristol Bay side of the Alaska Peninsula, there's a well-known hot spring located on a remote sea cliff. This site has been known by local native inhabitants for thousands of years and layers rich of broken shells with artifacts are some 12 feet thick. When we worked that area, we routinely went there at the end of the day to soak in the hot water. We heard about a natural gas seep very nearby along the shoreline, but had difficulty locating it. One-day Lee decided to go swimming in the ocean to see if he could find it there; and he did, right before he bumped into a humpback whale. He scurried out of the water and told us of his discovery. We figured that if we came back on a super low tide, the gas seep would be exposed above water and we could have an organic barbecue on the beach. We planned everything just right and caught a couple red salmon and went back to Port Moller and cooked our fresh salmon on the gas seep one evening and had a very special fest.

Grizzly bear will eat almost anything. Salmon is their preferred food, but when salmon aren't running, they eat rodents, grass, berries, seaweed, and more. They often find a salmon berry patch and gorge themselves with berries, then fall asleep on the tall grass in the sun. Lee told me that in the Urals, the natives sharpen eight-foot-long forked sticks and hide in the tall grass along bear trails near salmon berry patches waiting for a lumbering bear to wonder homeward. When the bear nears, they spook the bear, the bear rears, then lunges at the native. The native anchors the forked stick on the ground and it punctures the bear's lungs as it lunges at the native in the grass. Sound crazy? One day Lee and I had it out because I refused to let him try this after

work.

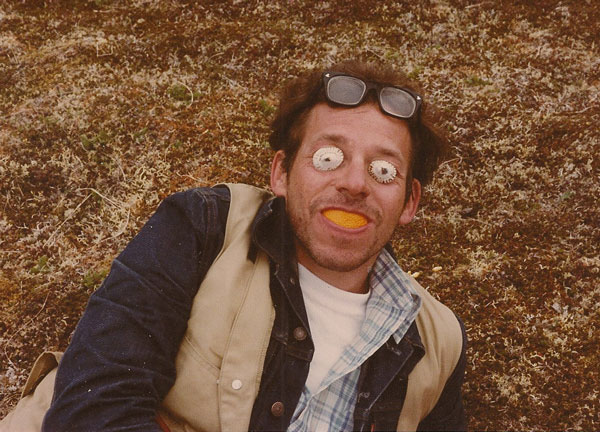

He was a wildman and we gave him lots of latitude. I remember flying over the Aleutian Mountains and Lee was sitting on the back seat behind me and he started shaking my shoulders and pointing down at something. At first I thought the helicopter had a mechanical problem. It was very noisy in the helicopter and we couldn't talk, but I finally figured out he was talking about a partially thawed pond below us. It was June and it had started to thaw and now had a tongue of ice extending from the shore down into the water. Lee seemed to be asking to land to go swimming in the pond. I thought he was bluffing, so I ask Eric to land. We landed and Lee stripped down to his undies, then carefully put his privates into his insulated leather glove, and slid down the ice tongue into the freezing water.

We spent a week at Iliamna Lodge on the northeastern Bristol Bay Lowlands while we studied rocks at the Lower Cook Inlet. These are just names to the reader, but Lake Iliamna is 20-mile-wide by 60-miles-long and located some 70 miles across the Lowlands from Shelikof Strait and Cook Inlet, so the daily flights were long. What's more, Katmai Park, Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and McNeil River Game Refuge were along the way (all Federal parks), which meant no firearms were allowed. Everyone knows about McNeil River and all the grizzlies; and they were telling us not to carry guns?! That was a non-starter. But the area was quite remote and no one was out there to see if we had guns or not, so we didn't worry much about the regulation. The region was nothing short of spectacular. Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes was full of tiny low-relief volcanoes that continue to steam and was quite amazing. It reminded me of maar volcanoes (described by Aaron Waters) that erupt in shallow water or sediments high in the water table. I'd enjoy going back there someday and studying these rocks rather than just flying over them.

We worked the area for a week, and on our last day, Eric (the pilot) got deathly ill right after lunch. We were stranded there many miles from civilization. The helicopter radio only works while flying, and then only for short distances, and we didn't have an emergency radio beacon. Eric was vomiting violently and having convulsions, and Lee and I didn't have a clue what to do for him. We wondered if he had food poisoning, but we all were eating sack lunches prepared back at Iliamna Lodge and Lee and I felt fine, so far. But Eric couldn't fly, and were in bum Egypt. We laid him on the tundra and covered him with a float coat and he trembled. After an hour and a half, he abruptly got up and said “let's go”, and proceeded to get in the helicopter and fire it up. We were apprehensive to say the least, but our choices were few. He flew, but not well. He stayed very close to the ground and was making erratic movements. He kept it up for about 15 minutes then landed hard and barfed some more on the tundra and resumed shaking under a float coat. At this point we still were about 40 minutes by air from Iliamna Lodge in a totally remote area, with no communication and plenty of bear.

About an hour passed before I climbed into the pilot's seat and started the turbine. Starting an Alouette is easy, especially after riding shotgun for a summer and watching. Eric had let me work the stick several times while we were in the air and flying seemed straightforward. The rudder pedals were a snag. Never had done that.... Getting off the ground would be the big challenge. Then getting back on the ground would be the next trick. Bad idea; what was I thinking. So we waited another hour and Eric had another burst of energy. We loaded up, fired up, and flew back. As we flew over the lake, we were only a few feet above the water and it was frightening. We had pontoons, but at our speed, we would have just flipped. The lake was about 20 miles wide at that point, and as we flew over the water, I looked back and saw Lee had removed his boots and had on a float coat and was ready to go into the drink.

We didn't quite make it to the lodge, but we did make it across the lake to the far shore. I went off and found an old pickup truck and loaded Eric and drove him back to the lodge. The weather was poor so IFR flight rules were in force and no local planes could fly Eric to the hospital in Anchorage. We called Anchorage and were able to dispatch a Medevac Leer jet which was able to land on the small dirt airstrip at Iliamna (just barely) and fly Eric back to Anchorage. Eric spent 14 days in the hospital and we never found out what was wrong, but suspect it was a malaria relapse from his time in Vietnam.

One of Lee's many stories he shared with us was about a field season years before in the northern Urals. They would fly the geological field party to the headwaters of a major river in a broad-bellied helicopter and drop them off with their supplies. They would have guns, rafts, some food, Geiger counter, and the like, and spend the season mapping their way down stream. They would hunt big game for most of their food, and store the meat on glaciers. Lee told me of a glacier where some of the annual black layers (varves) were radioactive. Being a geologist, he documented which years in the ice were radioactive. During the following winter, he presented his findings to a military officer who became alarmed and ask him where he obtained this sensitive information about radioactive fall-out. Lee answered in his smug way “from the rocks”. Lee did not get the last laugh this time though.

As the story ends, Lee died many years later of Leukemia. I went to Russia for my first time in 1991 a few months after the coup and tried to track down Lee to share the excitement of my upcoming trip. I was devastated to learn from his widow that Lee died in 1990 and had withered away during his later years. She told me Lee was the last of his geological colleagues to die, all from leukemia. I told her the story about the hot streaks in the glacier in the Urals and we realized what had happened. It's criminal the government of USSR allowed geologists to work in such radioactive areas. I spent much the 1990’s working in the Former Soviet Union and always wanted to share my adventures with my friend, Dr. Leonid Smirnoff.

Go to Chapters 7 & 8

|

Bear Lake Lodge from the air, looking south toward the Bristol Bay Lowlands.

Bear Lake Lodge from the air, looking south toward the Bristol Bay Lowlands.