|

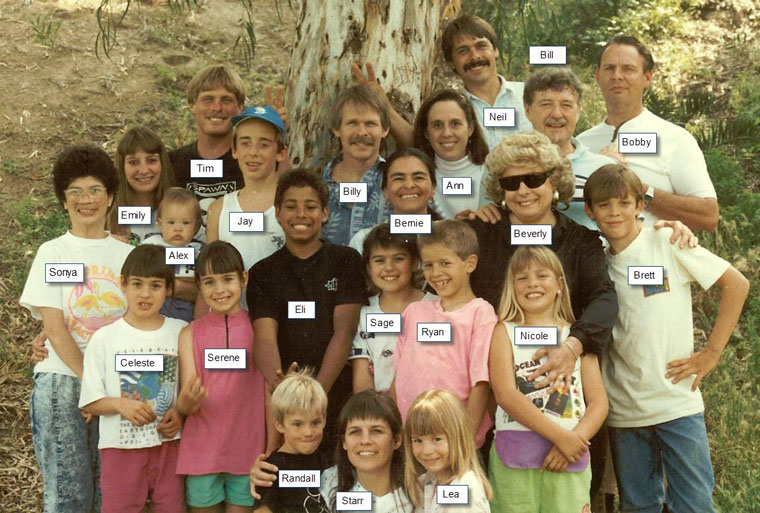

A. Bobby In 1948, Bob and Beverly Connelly and their two sons, Bobby who was three, and Billy who was two, lived in student housing in Temple City, California, while Bob attended Caltech in Pasadena. On Saturday October 2nd, their lives changed dramatically. Bobby and Billy were wondering about the housing project while Beverly was cleaning house and Bob was working in the nearby genetics farm. There weren't any witnesses to say exactly what happened next, and a two-year-old could not explain, but circumstances suggest the following.

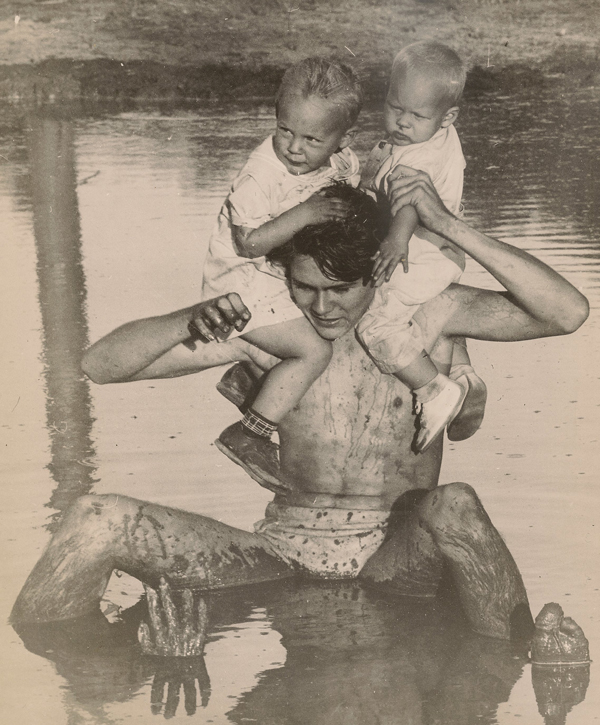

Caltech "Mudeo" in mid January 1949 during Bob Connelly sophomore year. Billy and Bobby Connelly on Robert Connelly's shoulders. Who's hand is coming out of the mud? While playing, the toddlers wondered into a construction site for Caltech student housing where a pit for a newly dug cesspool was left open and dangerously unsecured. The boys climbed into a wooden box on loose soil on the lip of the hole with Bobby in front and Billy in back. The soil gave way, causing Bobby to lurch forward and fall 30 feet to the bottom, leaving Billy in the box at edge of the hole, unharmed.

This is the scene of Bobby's accident.

Bobby sustained major injuries from the fall, was in a comma for two weeks, and nearly died. He had multiple broken bones, including 11 ribs, a collarbone, wrist, seven fractures of the skull, and a major concussion. He suffered some brain damage and remained challenged for life. To this day, Bobby has a silver plate in his temple where it was shattered from the fall. (Parents take heed and watch your children every second less the most unlikely situation harm them and forever change their lives.) This is the account of the accident my mother told me (and seems to document in her diary ), and the account I believe. Bobby once told me he thought I pushed him into that hole. I hope that is not so. In 2012 (after completing this Chapter), Starr gave me a copy of Mom's 15-page diary written between February 4, 1948 and November 10, 1950, which fortuitously chronicles Bobby's accident and events before and after. It captures her state of mind at 19 and 20 years old when her two wild toddlers were out of control and how she tried in vain to control them. She describes many 'near misses' before and after Bobby's accident and the reader gets the feeling it's a wonder either of her sons survived. Mom never let on to me we were so wild. An isolated entry dated 11/10/50 is so uniquely 'Bobby', I'll extract it here since most readers won't read the entire diary. Bob was teaching the boys their numbers. He explained to them, "If I wrote numbers all today - all tomorrow - all the next day, etc. - I'd never run out of numbers." Bobby looked puzzled and said, "but Daddy, you'd run out of paper."

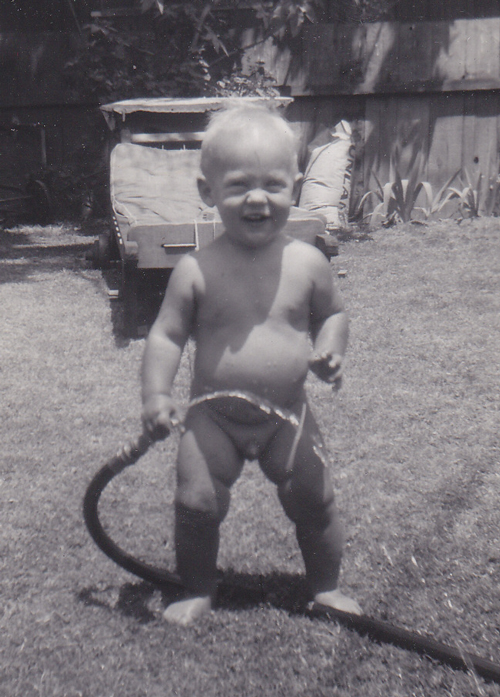

Father Bob and Bobby at about 15 months age, about October 1946.

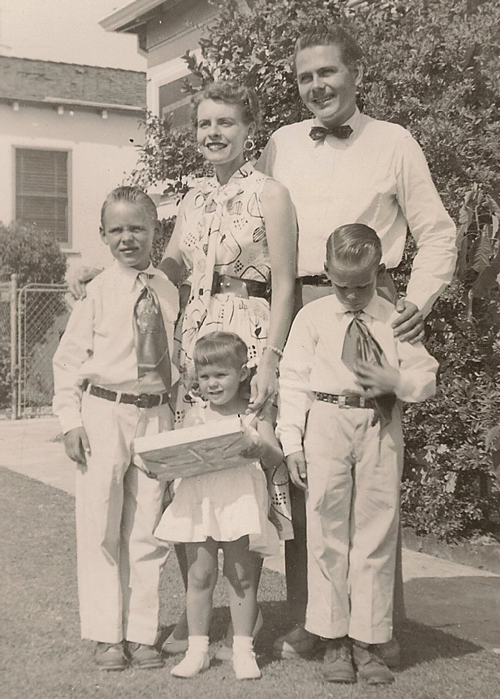

At the time of the accident, Dad and Mom were 22 and 20 years old, respectively, and not ready for challenges of the tragedy. Dad earned a BS in chemistry from Caltech June 6, 1951 and went to work for Shell as a lubrication engineer. The family grew with the arrivals of Starr 9/5/50, Duane 4/20/53, Neil 11/22/58, and Tim 2/4/64. Mom and Dad did a good job of providing a stable nurturing home for the children through the early 1960's. We always had grandparents over for the holidays, went on family outings, participated in the Indian Guides, Cub Scouts, and Boy Scouts, and attended church on Sunday.

Bobby, Starr, and Billy Connelly.

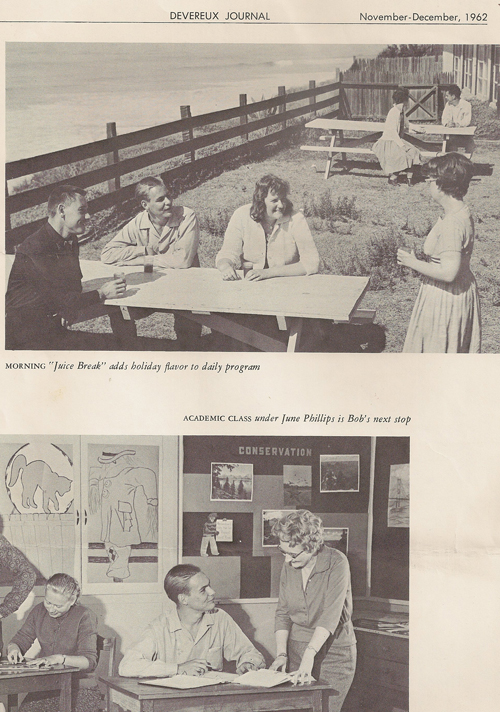

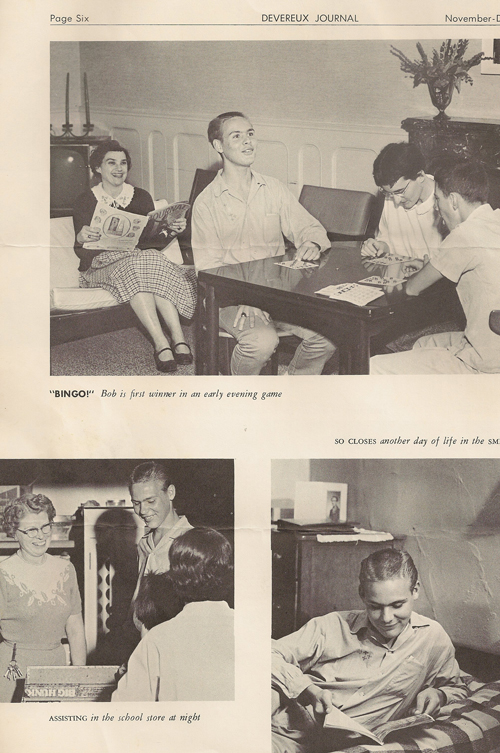

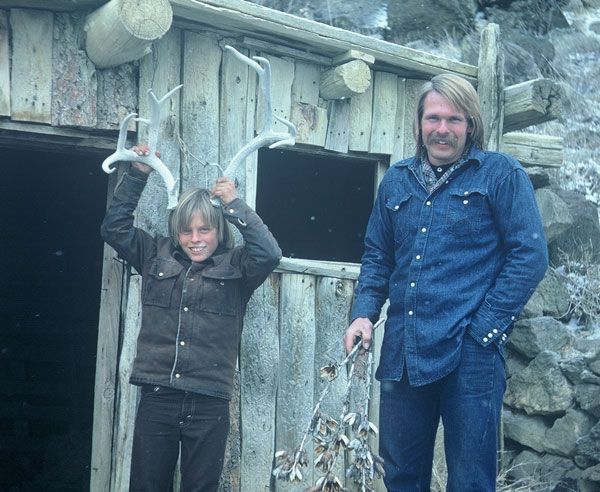

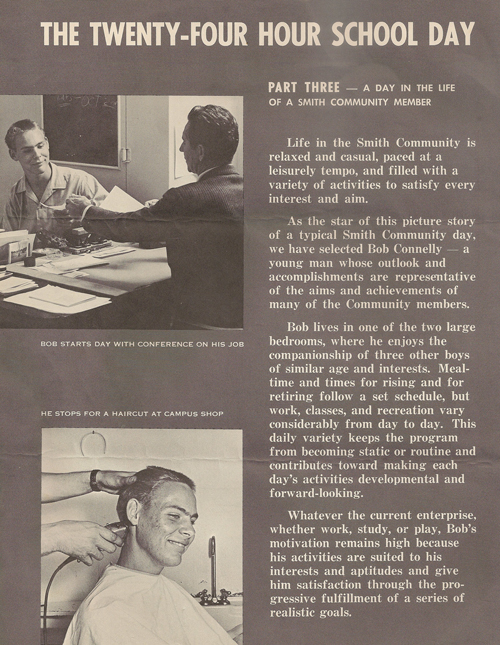

Bobby required special education in public school and tutoring at home. I remember helping him often with his homework; Mom helped him a lot too, but Dad generally didn't have the patience. Bobby's handicap was odd though, and he'd often surprise us with his asymmetric intellect. A good example was his geographical memory. When the family went on road trips, our parents never would tell us where we were going so we would try to guess based on landmarks along the way. Without fail, Bobby would always guess the destination first. Another example was his ability to work with wild animals. I've watched Bobby catch gophers with his bare hands. For those who haven't handled gophers, they're mean and require gloves, but Bobby never got bit. He also worked our beehives without protection, and was only rarely stung. It's my belief his accident damaged only part of his brain, not all, and he was abnormally gifted. Bobby was a very loyal brother and it was unwise for anyone to threaten me when he was near. He was big and strong, and when he was mad and had his arms around you, you were in big trouble. He didn't fight like everyone else. He had his own style of headlocks and scratching and biting, and he didn't know when to stop. Anyone who fought with Bobby was going to get hurt, no matter what. In 1962, Bobby enrolled in Deveroux School near Santa Barbara. We missed him while he lived away from home, but he did well with the specialized education provided at Deveroux. He learned to work with orchids, a trade at which he made a living for many years. He met a young girl there, Gail Hill, and was married in 1964. They remained married a number of years, but had no children and divorced.

Deveroux had a special issue about Bobby Connelly and here are three pages from that issue.

In 1985, Bobby married Sonia Blanco, and they remain married today. Sonia's family immigrated to America from Nicaragua and her two younger sisters are dentists in southern California. Sonia is a charming gal and we are proud to have her as a sister-in-law. She has her own challenges due to a traumatic birth and a childhood stroke. Bobby and Sonia have one son, Alexander, who was born in June 28, 1989. Alexander is about 10 years younger than my girls and I was flattered when Bobby asked me to be his Godfather. I recall attending the church near their home in Azusa for the baptism and being impressed at what a cute blue-eyed boy I had for a nephew.

Sonia's sister, Sonia, Bobby, and Billy, at their wedding in 1985.

While attending grade school and middle school, Alexander was a discipline problem and had to move between schools several times. Bobby and Sonia were at their wits end and couldn't come up with a proper solution to stabilize his education. In desperation, he was prescribed Ritalin for Attention Deficit Disorder. Bobby resisted this and discussed it with me on several occasions. It wasn't until Alexander was transferred to the Pomona School District and the Principal there took an interest in him that the problem was resolved. Alexander was given a battery of special tests and it was determined he was a genius. Once recognized, he was placed in special accelerated classes and his disciplinary problems ceased (without drugs). In the end, Alexander skipped high school and received an equivalent education from California State University at Los Angeles in a very short time. He went on to earn his Bachelor's degree from Cal State. This wasn't easy for Alexander since the family lived in Azusa, which is located in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains some 20 miles east of the campus. For several years, Alexander took the city buses across town to college, first for his high school, then for his BS. After graduating, Alexander wanted to become a Medical Doctor, but at 19-years of age, Medical Schools didn't consider him mature enough for the stringent curricula. Therefore, he worked as a biochemical technician at Caltech, a paramedic for an ambulance company, and a tutor for students at Cal State to earn a living while he waited for acceptance into Medical School. Alexander recently graduated with honors from Medical School at Colorado University, and we’re proud of Bobby, Sonia, and Alexander for this huge achievement.

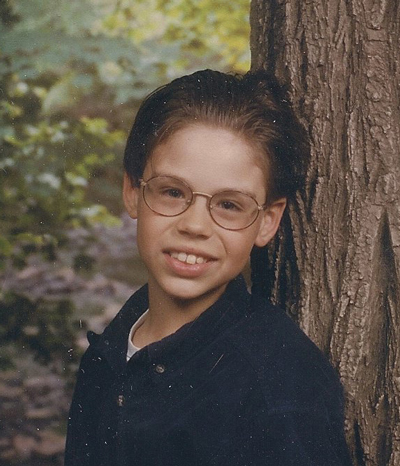

Alexander Connelly, 2010 interviewing at University of Colorado Medical School. Thus is the saga of Bobby and Sonia. Clearly both were blessed with good and intelligent genes, but for no fault of their own, they were not manifested in their own lives. Alexander is living proof of their genetics. I told Bobby once that he must have good genes to sire a genus, and he answered, "I don't know about you, but I wear my genes". As I said in an earlier chapter, Bobby encouraged me at a critical time in my life to earn my Ph.D. by saying, "Billy, you know I can't ever do anything like that, so please do it for me". That unfortunate childhood accident deprived him and the world of a powerful mind, but now his son is carrying those genes, with impressive dignity.

"What do you want to do?" "I don't know … I've been bored ever since summer vacation started last week." "Me too." "Let's drive somewhere." "OK, where?" "I don't know." "Do you have a map?" "Sure, there's one right here." Gerald Ginn opened a map of western USA and we gazed at it a few minutes before I said, "OK, let's close our eyes and each of us will put our finger somewhere on the map; then we'll drive there."

Billy Connelly and Gerald Ginn at Knott's Berry Farm. We agreed this was a good plan and proceeded. When we opened our eyes, my finger was near Searchlight Nevada, and his was near Desert Center California. Our destiny was set for the next week as we climbed into my '49 Plymouth and drove through the night. In the morning, we called our parents from Palm Springs and informed them we were going snake hunting in the desert and would be back in a week or so. We were only 16, but this came as no surprise to them since we were notoriously restless and loved the desert and reptiles and driving. Snake hunting had been our passion for several years now and we'd become quite good at it. I say 'snake hunting', but in fact, we collected all reptiles and amphibians. We memorized the scientific names for most local species and traded them to reptile dealers in Florida for their local species. Then we sold the Florida snakes to local pet shops for a considerable profit. We fancied ourselves as amateur herpetologists. In earlier years, we rode our bikes or hitchhiked up into the mountains above Arcadia, Pasadena, and Azusa and collected in the chaparral. Now we had cars and our horizons had greatly expanded. The Palm Springs area was our favorite since it was only 100 miles from home, but the Anza-Borrego desert was also good. Desert snakes all are nocturnal, so our 'MO' was to start cruising the back roads at dark and continue through the mid-morning hours. Nocturnal creatures fear moonlit nights since the owls were hunting for them, so we only hunted on dark nights. (A little known fact is that a full moon is seven times brighter than a half-moon.) We'd drive at 30 to 40 mph with our eyes peeled for snakes and geckos lying on the warm pavement. Sometimes one of us would sit on the front fender for better visibility while the other drove. We collected Glossy snakes, Long-Nose snakes, Desert Kings, Sand snakes, Hog-Nose snakes, Liar snakes, Desert Gopher snakes, Rosy Boas, Desert Geckos, and Sidewinders. Sidewinders were the hardest to catch since their movements were unpredictable and they were very fast. We sold all of our rattlesnakes to “Snakey Joe” who milked venom from them and sold it to a pharmaceutical company for making anti-venom. Snakey Joe was as weathered a desert rat as anyone we'd seen. His arms were scared with little X's that were cut after being bit a number of times. He only paid us $1.50 a pound for rattlers, but visiting his snake farm made it worthwhile. It was “Snakey Joe” who taught me to catch rattlers bare handed. This was a great party trick and I performed it many times. The rattler needed to be out in the open with no place to retreat. After teasing it a bit, it would coil and get ready to strike. I'd take off my t-shirt and dangle it in front of the rattler with my left hand. The instant it struck at the shirt, my right hand came in behind it and grabbed the neck right behind the head. There was no room for error here since if you grab too far forward, you got fangs; if you grabbed too far back, the rattler twisted around and bit. This worked best on Pacific Diamondbacks since they are larger, slower, and relatively docile for rattlers. It didn't work at all for Sidewinders. Tonight we were collecting west of Palm Springs along our favorite route, which included White Water Road, Depot Road (Tipton Road), and Snow Creek Road. It took about 45 minutes to drive the complete route one-way, then we'd turn around and drive it the other way, again and again. We put the smaller specimens in empty one-gallon pickle jars, which came four to a box from Orange Julius. The larger snakes went into cotton snake-bags. It was a challenge keeping them cool during the day while we were collecting Desert Iguanas and Chuckwallas at the abandoned airport and Agua Caliente Canyon, respectively. We didn't have air conditioning and the heat always was over 100-degrees, so to keep them alive we kept them out of the sun, put damp towels over them, and left the windows open. We would collect for up to a week at a time, and we sleep on our wooden cots in the desert. Since there were many scorpions, tarantellas, and Sidewinders, we put the legs of the cots in coffee cans filed with water, which provided a mote of protection from venomous night crawlers. We preferred sleeping in the date-palm orchards near Indio where lemon trees were planted under the palms; this made it cooler and darker in the mornings. For food, we often ate Dinty Moore canned stew, which we warmed on the manifold of the engine for half an hour while we drove. We bathed in motel swimming pools late at night when nobody would notice. I'd converted our workshop into a snake room and had some 25-snake cages on shelves. Our old pinball machine was gutted and converted into a large terrarium. There were three large rodent cages where I bred rats and mice for snake food. The white female baby rats were sold to a local biology supply facility for research specimens at a handsome price (this alone paid for much of my hobby). One of the rats inadvertently got out of the breading cage. He was a very large hooded rat and he lived in the garage/shop/snake-room complex. With time, he became quite tame and loved people. When he heard the screen door to the back porch slam, he would scurry down from the rafters of the snake room and run out onto the patio to greet us. He would climb up and lick our legs. Ratsy was one of our favorite pets and we had him for about 3 years. We don't know what became of Ratsy; suppose he died of old age. At a different time, we had a free-roaming guinea pig. At first, my parents drew the line at poisonous snakes and wouldn't allow them on the property. The time I put two rattlers in the icebox crisper to hibernate is discussed even today by my siblings. The rattlers were in a snake bag tucked in the back of the vegetable crisper drawer and went unnoticed for several weeks. When finally my mother discovered them, I was read the riot act. As time passed, she got accustomed to me having a couple rattlers in my room. Reptiles weren't the only creatures lurking about the Connelly residence. We had a double lot at 6033 Camilla (Temple City) so there was plenty of room for a chicken coup and the like. My dad bought a dozen chickens and we tended them for eggs. When we finally got rid of the chickens, I got some homing pigeons from a friend and keep them in the coup. It always marveled me how these pigeons found their way home within hours from many miles away. Dad built a one-way door for the coup out of segments of clothes hangers so the pigeons could enter the coup, but not leave. After the pigeons, I kept a red fox in the coup, then a badger. From time to time, we would catch a possum and keep it in a cage. Possums are unpleasant creatures and very mean.

Our fort at 6033 Camellia; note the huge flagpole. I dug a small cement pond under a fig tree in the back yard where I kept a small alligator, and countless toads, frogs, and a snapping turtle. I recall the time I released several bags of baby toads mixed with a few tree frogs into the pond, only to learn the small tree frogs croak as loud as full-sized bullfrogs when the sun goes down. After some angry calls from neighbors, Bobby and I were forced to catch the frogs by flashlight.

Billy and Bobby Connelly. Of all my treasured pets, a Gila Monster was my favorite (besides our family dog). My friend Richard Dunn was older than me was and worked at the Nature Center in San Dimas, and he was the source of many of my pets. In the end, I traded Richard a nearly complete Lincoln penny collection for a magnificent Gila Monster. This remains the single worst trade I've ever made, but at the time it felt right. The Gila Monster was docile and we handled him daily. My dad kept honeybees and we had hives in a couple nearby orange orchards as well as in the back yard. We harvested the honey regularly and stored it in bottles. Both Dad and Bobby could remove honeycombs from the hives without protection. I was in awe and wished I had the nerve to try it. My mother became accomplished cooking baked goods with honey (rather than sugar) and won many prizes at the L.A. County Fair.

Dad showing scouts how to work with bees; Bobby and Dad without protection; me with protection. From the time I was 12, I always found regular work to finance my activities. My first job was a paperboy at the Santa Anita Race Track where I barked the afternoon Herald-Examiner to horse racing fans as they exited the track after the races. I rode my bike a few miles to and from the track after school. I worked there during racing season (December through April) until I was 16.5 years old. It was at Santa Anita I learned the evils of gambling, and to this day I won't gamble. What a bunch of losers and drunks who frequent the horse races. After the last race when paper sales trickled, I would go out into the vast 40-acre parking lot and help people find their cars on my bicycle. It was easy to forget where you parked, especially for those who didn't frequent the track. I charged $20 to find each car and often made more money doing this than barking papers. The year I turned 16 and could drive, I definitely made more money finding cars than barking papers. This is a good example of how at a young age I learned to become opportunistic. As discussed below, home life had become very rocky and I needed to be self-sufficient. I saved much of my money and always bought lots of gifts for the family at Christmas. One of my chores at home was to take the dirty clothes to the laundry mat a few blocks from home. When finished, I brought them home and hung them on the cloths-line in the back yard. One Christmas I bought my mom a washing machine and installed it the garage. I still recall counting my quarters and half dollars each day until there was enough to buy the washer. Mom was thrilled. My next job was at Fisher's Drug Store where I was a delivery boy and stock clerk. The drug store was only two blocks from home and my parents had known Mr. Fisher for years. I was given the family's old '49 Plymouth on my 16th birthday and used it to make deliveries. I worked at the drug store a couple years and was a dependable employee. Mr. Fisher instructed me early that "the boss isn't always right, but the boss is always the boss"; a lesson I remembered the rest of my life. Soon after graduating from high school in 1964, the Plymouth starting having issues with the engine. It began when I was trying to keep up with a speeding Cadillac on the way to Palm Springs on a snake-hunting trip. When finally we slowed down at the outskirts of town, there was a rod knocking. We took it to a service station and Gerald and I pulled the oil pan and replaced the bad rod bearing, but it never again ran the same. We decided the “tank” needed a makeover, which became a mission that lasted months. When finished, it was a piece of art even Salvador Dali would have been proud. The front end was raised a foot with spring spacers and mimicked the 'gas rake' popular with hot rods at the time. For hood scoops, we cut an orange road cone in half and duct-taped it to the hood in staggered positions like the Plymouth Fury 413 muscle cars. Exhaust headers were constructed from chrome Dixie cup dispensers, which we screwed into the sides of the front finders. We painted orange flames on the sides of the 'tank', covering part of the baby blue Earl Scheib paint job. All the chrome was also painted orange. We decided we needed a Continental kit and constructed it with a 20-inch bicycle tire bolted to the back of the trunk. Rear deck aerials were fabricated from sixteenth-inch steel rods stuck through holes at each side of the trunk. Inside the car, we made 'dingle berries' out of cotton balls and string and hung them around the windshield like the low-riders. A pair of combat boots was hung from the rear view mirror and the steering wheel had a thick fuzzy steering wheel warmer. We felt the 'tank' needed to be louder to attract more attention, so I gouged a couple holes in the muffler with a crow bar. We had such fun cruising Bob's Bigboy and Henry's Hamburgers along Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena. We often would slouch down in our seats like the low-riders in El Monte, and sometimes we wore straw sombreros we bought in Mexico during one of our many road trips to Ensenada. At home, my parents weren't getting along and decided to divorce. I was 17 and a senior in high school when it was finalized. I won't dwell on this unpleasant time, but since it had such an impact on the family and me, I'll discuss it briefly. Dad immediately left the house, x-wife, and kids and never looked back. He was gone gone gone. Mom conceived a baby in the twilight of the marriage, but didn't know of it at the time of the divorce. When she came into labor, I took her to the hospital and waited in the waiting room during birthing. Dad didn't see Timmy until he was several years old and I was the proxy dad. There were six kids now with no father or regular source of money. My mother took to drinking and became an out-of-control alcoholic. These years were very hard for Mom and the kids and I choose not to discuss details. I recall a number of times people from the church would bring food to the house. My bicycle, then my car, was my way out of that crazy house. However, it hadn't always been this way; in fact, in earlier years we had a great family life. Bobby and I joined the Indian Guides, then the Cub Scouts, then the Boy Scouts as the years went by. Dad always took leadership roles in these events and we had many great trips and camp-outs. We went to swim lessons at the Caltech pool in Pasadena most weekdays during the summer and all the kids were good swimmers. The pool was open to Caltech alumni and the instructor (Mr. Emery) was one of the best swimming instructors in the State. I joined their swim team and became an excellent swimmer and could swim all strokes competitively. They asked be to become one of their swim instructors and I taught young kids to swim. I even took their life-saving course and became certified as a lifeguard. Dad had a fetish for boats and we spent most of our weekends at the ocean water skiing, fishing, or traveling back and forth to Catalina Island.

Dad entertaining the cub scouts.

During the summers of 1963 and 1964, I worked at a church summer camp in the San Bernardino Mountains as a lifeguard. Loch Leven was a wholesome experience for me and I lived there all summer with the other staff. It is here I met my first girlfriend. Prior to this, I'd shown little interest in girls (perhaps because they'd shown little interest in me). One of my front teeth was broken off and I was a bit chubby and I didn't care much what I wore, so chasing girls seemed futile. At 15, I lost most of my excess weight and finally my parents paid to put a crown on my broken tooth (after four years). Yes, now I found someone who thought I was interesting and attractive. I don't recall if Marcia Bickford and I ever kissed during our time at Loch Leven, but we were best buddies. Even though she lived 20-miles away in Whittier, our relationship continued until I went in the Navy in 1966, when it ended abruptly.

Larry Miranda and Bill Connelly at Morro Rock, 1971. Glenn Gray and I first met when we were 15 or 16. Glenn lived very close to Gerald in El Monte and they attended Rosemead High School together. Gerald, Glenn, and I became the 3-musketeers and did everything together. As I phased out of my snake hunting years, I spent more and more time at Glenn’s house working on his dune buggy, then his Jeep. He had a fine CJ-5 and we installed a high performance 289 engine to make it very fast. We also put in a 4-speed transmission with Hurst linkage, wide off-road tires, posi-traction differentials, custom stainless dash with Stewart-Warner gauges, and a roll bar. Good thing he installed the roll bar because he rolled it end-over-end a week later while climbing a very steep hill. Glenn’s garage had every tool you could imagine, including an acetylene torch and an arc welder. We spent months building the Jeep from the ground up. When we finally put the body on and configured the new dash, we were quite anxious to see if it ran. It started right up and we took it out on the street to test it. I still recall the look on Glenn’s face when he turned the steering wheel right, and the Jeep went left. We don't know how it happened, but somehow we installed the Pitman arm backwards. You really need to try driving a car sometime with the steering setup backwards.

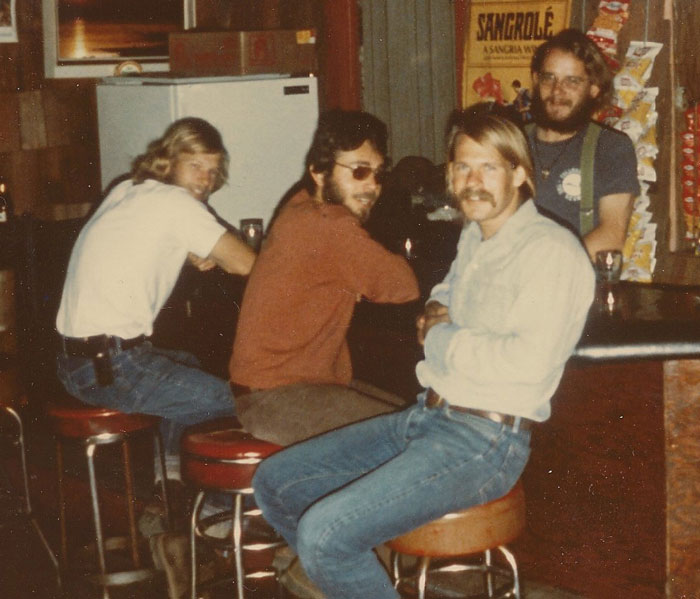

Glenn Gray, Larry Miranda, Bill Connelly, and Richard Davies (Leroy Latta took picture), Humboldt County, "bear hunting" expedition. Glenn belonged to a local Jeep racing club where we met Leroy Latta. Leroy was six and a half feet tall and drove a Jeepster wagon souped up with a huge Oldsmobile engine and a racing B&M hydromatic 4-speed transmission. He fit right in with our group and joined us on many excursions. After the Navy, Glenn and I attended Cal-State Hayward and earned B.S. degrees in Geology. We roomed together for two years in San Leandro and attended countless rock concerts in San Francisco at the Avalon Ballroom, Fillmore West Ballroom, and Cow Palace. Gerald traveled a different path during these years and engaged in illegal activities for a time. After that, he became a very successful salesman for Century 21 Real Estate. One year, he was the number three salesman for California. Aside from an epic weeklong road trip from southern California to Cabo San Lucas in 1979, I saw very little of Gerald in later life. But this road trip was a memory maker. Gerald, Glenn, and I drove his old pickup truck towing a 27-foot sky-cab fishing boat along those very narrow and dangerous 2-lane roads in Baja California. The truck swayed badly due to the boat not tracking well, and it was a challenge keeping it in our lane when large trucks and buses came from the other direction. I came up with a good solution when I held a bottle of Pacifico beer near the windshield so the oncoming vehicle could easily see it. The bottle, combined with our perpetual sway, led the drivers to believe we were out-of-control drunk; so they would move as far as they could to their right, giving us another foot of road. This was a one-way trip for the truck and boat (which I came to believe were stolen), so we flew home.

Bill Connelly and Leroy Latta, Havasupai, spring 1973.

Glenn Gray, Bill Connelly, and Gerald Ginn, Baja California road trip, 1979.

“Did you hear who was killed in Vietnam a few days ago?” “No, who?” “Craig Schoenbaum, and he was only over there three months.”

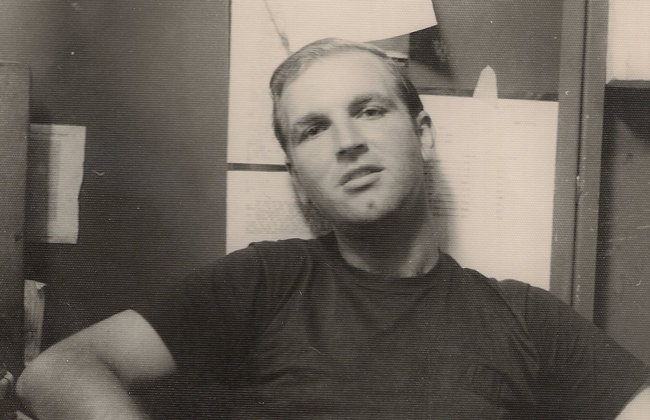

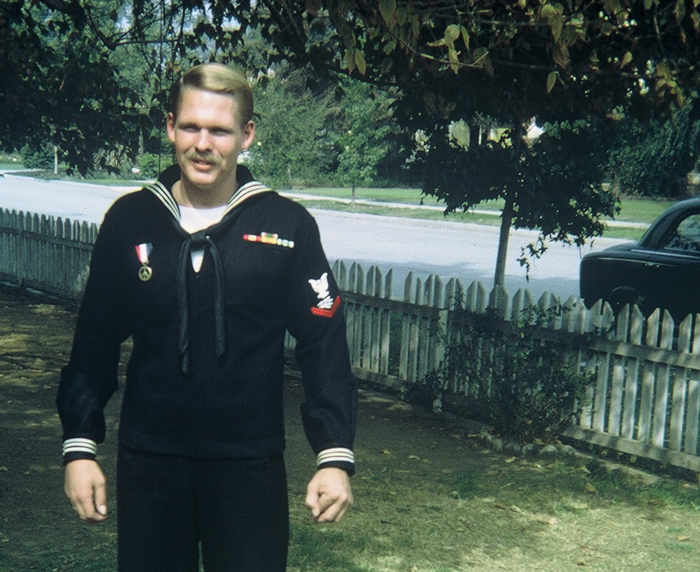

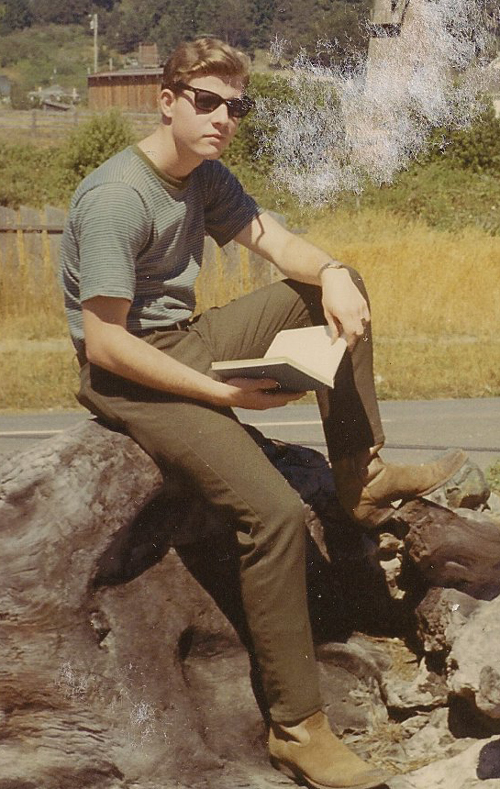

Bill Connelly at Mom's house on Camellia, Temple City, October 8, 1968, after being discharged from active duty. Note peace medal on right chest. Gerald Ginn, Glenn Gray, and I were sitting at a table in the student lounge at Pasadena City College having our morning coffee and donuts as we waited for our next class to begin. This was a ritual for us since we were taking only 12.5 units and had plenty of time between classes to socialize. “Yah, and George just lost his II-S student deferment and got a I-A. Sam had his I-A classification only four months before they drafted him into the infantry.” “Well, I still have my II-S deferment, but I'm really worried about it. If they look at my records and see I'm only taking 12.5 units, I'm fucked”. “Me too.” “That makes three of us.” We graduated from high school in 1964 and it now was 1966 and our second year of city college. We'd been lax about maintaining a full-time status of 15 units since we had other important things to do, like drive around and play guitars and sit in student lounges and stuff. All young men were required to register for the Draft when they turned 18 and now there was a huge demand for us in Vietnam. President Lyndon Johnson signed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August of 1964, which provided for him to take “all necessary steps to repel any armed attack against forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression”. In other words, this provided authority for all-out war against North Vietnam. By 1965, the troop level in Vietnam exceeded 200,000 men and boys. “Maybe we can sign up for the Coast Guard or something … anything but the army.” “No, the Coast Guard hasn't taken anyone for months.” “Well, there's always Canada ….” “I'm game.” "Then there’s the Navy, but that's a four year hitch." “What about the Navy Reserve, it's only two years?” “They've been closed for months too.” “Yah, but I just heard someone this morning say the Pasadena office opened yesterday for a few new recruits.” “Really?!” There was silence as we all digested this possibility and studied each other's expressions. This would require an immediate unplanned decision; one that would dramatically change our lives. I don't know who spoke first or if we all just got up and went to my car, but before I knew it, we were driving to the Reserve Center a few blocks away in Pasadena. We were dressed for school in our usual low-life attire of shorts, thongs, T-shirts, long hair, and several days’ whiskers when we walked into the recruiter's office. The Petty Officer looked at us with a bit of apprehension and asked what we wanted. Gerald answered with a smirk only he could produce, “we want to join up”. The PO said we needed to pass some tests first. From his body language, I don't think he thought we'd do very well with the tests and he'd send us on our way. We took the tests and did quite well. Fact is, we did so well, we qualified to go to special schools and we all chose electronics school followed by radio school. It was April 28, 1966, and we signed the dotted line to become Navy Radiomen; now we were driving home to tell our parents.

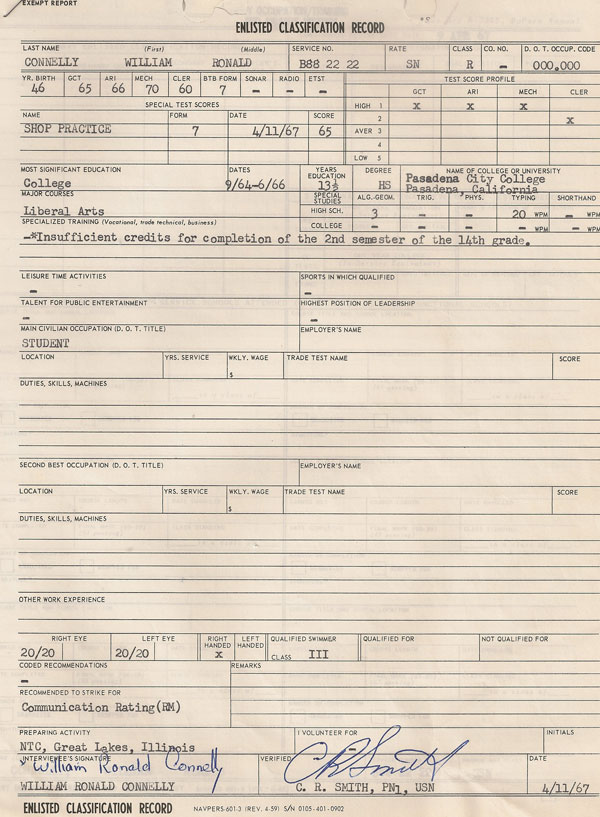

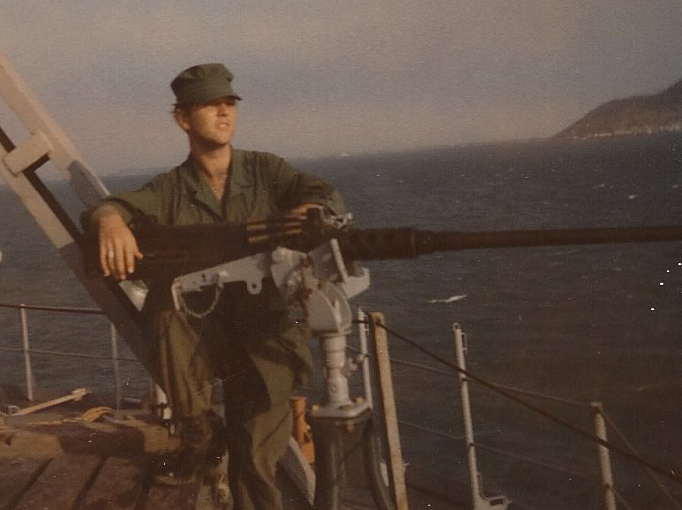

The deal with the Navy Reserve was we were to attend monthly meetings in Pasadena for one year, then we were to go on active duty for two years, then we were to be on inactive reserve for three years, for a total commitment of six years. We were issued our Navy ID cards that day and mine was lucky number B88-2222. In August, we were issued orders to Boot Camp in San Diego for two weeks. This was a gravy train since the regular Navy went to Boot Camp for six weeks. We had a hair-cutting party the night before we departed for Boot Camp since we didn't want the Navy to have the pleasure of cutting our hair. I don't know how many six-packs were emptied before settling on our new hairstyles. I had a scalp lock, Gerald had a Mohawk, and Glenn was fully bald. Sure, we looked stupid, but the barber at Boot Camp was robbed of his sadistic pleasure of buzzing these three Reservists the next day. They were limited on how much spirit breaking they could impose in just two weeks of Boot Camp, especially on the likes of Gerald, Glenn, and me. We were assigned to the same barracks and we had a ball. Reservists had to wear white leggings and everyone looked alike with the blue dungaree shirts and pants, and white sailor hats. We quickly learned to take advantage of this since we could disappear into a crowd so easily. There were Petty Officers patrolling the ‘grinder’ on bikes looking for someone doing anything wrong and they would chase them down and make them do stupid things like move a sand-line. (There is this pile of sand and a shovel. One fills two buckets with sand and carries them about 200 feet and empties them into another pile. Once the sand pile is moved, one then moves it back to its original location.) We would do something overtly wrong and draw one of the PO's to chase us, then cut through a barrack and disappear in a sea of swabbies. In April 1967 when it came time to go on active duty, Glenn and Gerald went to schools in San Diego, while I went to two months electronics school at the Great Lakes Training Center near Chicago, followed by three months of radio school at Bainbridge Maryland. They made me a Section Leader at radio school, which was the first time I'd ever had a leadership role. It was forced on me; I suppose because I'd done well on the various tests they'd given me at the recruiting center and in electronics school. It worked out all right and I became aware of a part of me I'd never known. We learned Morse Code and typing in radio school and by the time we graduated, I could take code at 26 words per minute, and type at 55 words per minute. Glenn, Gerald, and I received very different orders following our Navy schools. Glenn fared best and went to the Navy Communications Center in Hawaii for the rest of his active duty where he surfed and enjoyed the good life. Gerald fared worst and was sent to an unpowered supply barge on the Mekong Delta where he managed the radio when he wasn't shooting 50-caliber machine guns. I was given sea duty and assigned to the USS Oriskany in the Gulf of Tonkin.

Gerald Ginn on supply barge for Swift Boats on Mekong Delta. Back of picture reads: "Me on my 50-caliber mount, YR9 (YFNB-9); 26 Jan 68".

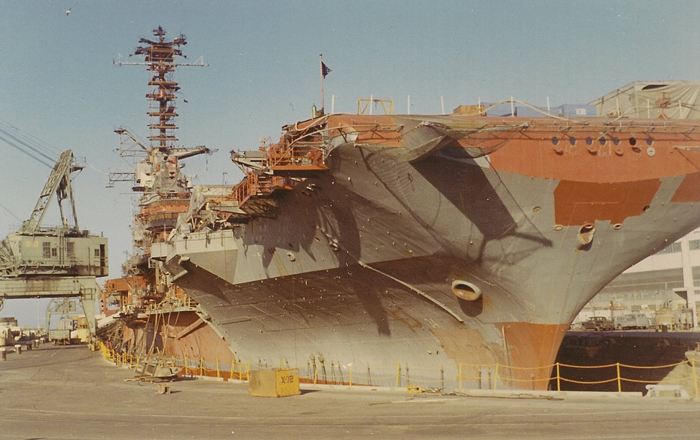

The Oriskany is an attack aircraft carrier and was already in “Yankee Station” in the Gulf, so I was flown to Subic Bay Navy Base in the Philippines where I waited for three weeks for a ship to take me to the Gulf. Olongapo City is just outside the gates of the base and was classic sailor's city for bars, whores, tattoos, and the like. Some say that if the world were to take an enema, it would be through Olongapo. I spent more time swimming and boating than carousing Olongapo while waiting for the USS Graffias to take me to Vietnam. Subic Bay Naval Base closed in June 1991 after the huge eruption of Mount Pinatubo just 20 miles away. The USS Graffias was a small refrigeration ship and was taking food goods to ships in the war zone in the Gulf of Tonkin. The radio crew was small and very friendly and I was excited finally to be under way. Unfortunately, we sailed into a typhoon several days later and that small ship was thrown about like a cork, and I was very seasick. I remained seasick for four days and no one bothered to call me for my duty. When the typhoon passed, the Graffias went about supplying food to ships in the Gulf. This was done by pulling alongside them and traveling at the same speed and running lines between the ships, then winching the pallets of food across. I recall one destroyer flying a red flag on its fantail next to the American flag that simply read “Fuck Communism”. However, no signs could match the banner on the side of the Graffias, which read, “You can mash our potatoes, but you can't beat our meat”. After three weeks in route, we reached the Oriskany and another typhoon was underway. It's Navy custom to high-line personnel between ships with “man power” rather than winches, so lines were drawn between the Graffias and the hanger deck of the Oriskany, and some forty men were pulling on the ropes on the Oriskany to keep the lines taught as the ships swayed in the swells. A cage big enough for four men was pulled on rollers along the top line by a lower line as the two ships traveled into the wind at about 15 knots. I was the last to high-line across before they decided this was a bad idea with the typhoon and all. To this day, that ride was the most exciting thing I've ever done. There appeared to be a mighty river below me between the two ships, and the winds howled and the rain poured and the cage bounced from the ships swaying in the huge swells. For the first time since that day at the USNR center in Pasadena, I felt like I was at war. The Oriskany was enormous and A-4 Skyhawks and F8 fighter jets were crowded on the hanger deck with crews of sailors loading bombs on them. Old piston engine single-prop Spad bombers were crowded to another part of the hanger deck with their wings folded up and large bombs already fitted beneath their fuselages. Airedales (Navy airmen) were hustling about tending the aircraft preparing them for the next day's strikes. I was taken through this factory of activity to a series of ladders that lead us to the communication center where I met my new Chief Petty Officer. After assigning me to the duty roster, I was taken to my new quarters on the fourth deck below where I was given the top bunk on a stack of five. I knew this was a problem, but for now, there was nothing that could be done since the cabin was full and most of the sailors were sleeping. It was October 1967 and I was 20-years old, but sadly, bed-wetting remained a problem. This was my big secret and I went to great lengths to keep it that way. If I didn't drink for several hours before going to bed, there was a 90% chance no problem would occur. However, these bunk beds were canvas and it would be impossible to conceal even the smallest slip. In retrospect, bed wetting was grounds for a medical deferment; wish I would have known that at the time …. The next couple of days were spent trying to figure a way into a bottom bunk, but it seemed everyone desired a bottom bunk and I was the new guy on the block. I pulled the heartstrings of a homely young guy by telling him the story of how I rolled out of my bunk bed when I was 11 and broke off my front tooth and got a bloody nose and knocked myself out, all of which was true. He swapped with me and my secret remained concealed. After a month on the Oriskany, I found an unmanned transmitter room below the flight deck with an attached catwalk and took up sleeping there. It was wonderful to get out of the crowded cabin and sleep on a cot on the catwalk above the ocean where it was cooler and the air was fresh. This was strictly against regulations, but no one was ever the wiser. Duty was 12 hours on, 12 hours off, 30 days a month. The communications center was air-conditioned which was nice, but it was full of cigarette smoke. I had a TOP SECRET security clearance and managed an encrypted radio teletype circuit for our task group, which included several destroyers and destroyer escorts. The old teletypes were slow and many of us could out type them, have a drink of coffee while the TTY caught up, and then resume typing. They were mechanical marvels and it took specialized radiomen to repair them. They offered to send me to TTY school (which was an honor), but it required a six-year commitment so I declined. (They also offered to send me to pilot's school with a six-year commitment, and I declined.) We had an Admiral onboard, so we sent FlightOps reports to the States each day telling how much death and destruction we caused that day; and how many planes and pilots were lost. An interesting aside is that John McCain was a Skyhawk pilot on the Oriskany and was shot down on October 26, 1967 over North Vietnam where he had several broken bones and was held prisoner of war for five years. I would have sent this report as part of the daily FlightOps. There were 3500 men onboard the Oriskany and it was a floating city. You could find a cobbler, soft ice cream, laundry, post office, mess deck, flight observation deck, and more. There wasn't much time for recreation however with our “Yankee Station” duty schedule. Planes were continually being launched with the catapults and returning from their bombing raids. Some would return all shot up and have holes in their wings and wounded pilots. Occasionally it was so bad they would put up a huge net across the flight deck to catch a plane in case its hook missed the retrieval line along the flight deck since there was a poor chance the pilot or plane was good for a second attempt. While we weren't on shore where the real shooting occurred, we lost a fair number of our pilots. Sailors died due to odd accidents like being sucked into a jet intake, walking into a prop, over filling an aircraft tire and having it blow up, and fires. There was a major fire on the Oriskany several months before I boarded that killed a couple dozen pilots who didn't know their way around in the dark and smoke filled decks and suffocated. Since then the Big "O" was nicknamed the Crispy "O". Our first R&R was in November in Hong Kong. It was short, but I was excited because it was my 21st birthday and my friend Pat Murphy from high school was going to be there. He was on one of our destroyer escorts and I learned of his presence through an unauthorized radio teletype chat with their radioman late one night when I asked if he knew of anyone onboard from Temple City California. It was wonderful to see Pat and we had a grand time touring Hong Kong for a few short days before we headed back to the Gulf.

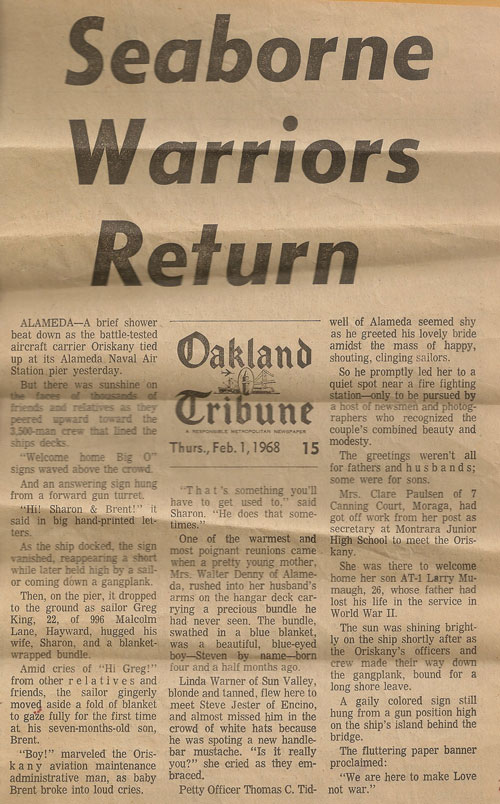

Pat Murphy in Hong Kong. I was promoted to a radioman third class Petty Officer in April 1968 and was proud to have a crow on my sleeve after only a year of active duty. This however was not enough to relieve me from the bomb-loading details we were routinely assigned to after our 12-hour shifts. No problem for me though since I had a second-class PO coat I'd been wearing to these details right along anyway. As an apparent second-class PO, I just had to show up and watch, not load. I took advantage of the fact the ship was so large that other Divisions wouldn't know anyone and my name appeared on a duty roster without a rank. I can honestly say, I've never loaded a bomb or pealed a potato. As a radioman PO3, my responsibilities were elevated and I was enjoying the job more. I memorized the common Z and Q commands and could rattle them off to the task force network when necessary. “ZKA ZKB ZAA QRL”, I would tell the unauthorized radio transmission, then my signature “KKKKBC”. When it came time for CW drills (“continuous wave”, or Morse Code), I always was nominated to represent our ship. It was fun to work the key during these drills and I usually did well. If I messed up though, no problem: I would just reach over to the Top Secret radio TTY and send a note to the other radioman on the drill and say “hey matey, missed those last couple words: help me out here”; and he would repeat his CW transmission, only on the TTY where the radioman monitoring the drill couldn't see. 'Join the Navy and see the world.' Besides the Philippines, Vietnam, and Hong Kong, we had two liberties in Japan at Yokosuka. Japan was a pleasure indeed and a very cultured country. However near the Naval Base, the local Japanese serviced the 7th Fleet’s every need as ships anchored for their R&R. The whores there were inspected by Navy doctors and proudly displayed their current health certificates in their places of business. It was here that I was convinced to join four horny radiomen to a whorehouse after a month at sea. The dimly lit lobby where we waited smelled of incense and was decorated with cheap Japanese tapestry. Finally I was called to go to a back room. When I entered the door closed behind me. Before me stood a nude over-weight Japanese woman in her 40’s smiling with several teeth missing, and bowing repeatedly as is the Japanese custom. Not only was I not aroused, I was repulsed, and it must have showed. I was 21-years old and still a virgin, and this was not working for me. As I turned for the door, she said in very poor English, “then how ‘bout a blow job sailor?” I kept going. This was our last port before our long voyage Stateside. As we were approaching the Hawaiian Islands in route to the States, the USS Pueblo was captured by the North Korean navy on January 23, 1968. North Korea claimed this “spy ship” strayed into their territorial waters, while the US maintained it was in international waters. Regardless, it was termed the "Pueblo Crisis" and someone needed to come to their rescue. The USS Oriskany was steaming nearby and we were a likely candidate since we had left “Yankee Station” and were sailing for the States. As radiomen, we were privy to all of this Top Secret stuff and were concerned about how it could affect our plans to go home. In the end, they let us continue on our voyage home and others came to their rescue. To this day however, the USS Pueblo is the only American ship in hostile foreign control. We crossed under the Golden Gate Bridge on January 31st and all the officers and men stood along the perimeter of the flight deck in full dress as we were welcomed by a few spectators. We docked at the Alameda Shipyard for a couple weeks, and then moved to Hunters Point Shipyard south of San Francisco where the Oriskany was put into dry dock for extensive repairs. Most ship personnel were released to other duty stations or moved to barracks on the base, but the remaining few in the Communications Division were some of the unlucky ones who remained on the ship during dry dock.

Ron Latshaw, Mike Brennan, and Szwarguiski were fellow radiomen and we became good friends during our time at Hunters Point. I recall little about them before our time at Hunters Point except Ski once telling us his parents were gherkin pickers. I'd never heard of a gherkin so I was amused to hear him describe the assembly line job of selecting the tiny pickles for special packaging as the pickles came along a conveyer belt. Latshaw bought an old truck with a camper and kept it parked near the ship, and that was our refuge whenever we could slip off the ship. I bought an old Peugeot 403, so we had good transportation options for going to San Francisco to see rock concerts. Slipping off the ship was easy for us since, as radiomen, we had special 'watch-stander's liberty passes and could leave the ship any time we were not on watch. And even when we were on watch, it was easy to slip out through one of the many opening in its haul that could not be seen by the watchful eyes of the quartermasters.

Ron Latshaw in Mendocino, CA, July 1968.

During my liberty, I sometimes would drive to the CAL Berkeley campus and try not to look like a swabby. I was a bit a hippie anyway if it weren't for the short hair. Even it was longer than almost anyone else since I kept it tucked away under my work cap. CAL was in the midst of the 'free speech' movement and students were out of control with anti-war demonstrations and free love and ultra-liberalism. It was too wild even for me, but a welcome break from Hunters Point. I recall the first time I went to the student union and a number of hippie students were listening to the evening news as they reported the daily American casualties in Vietnam, and they cheered. I was taken aback and left. It's one thing to be against the war, but something entirely different to cheer the deaths of your fellow students who were drafted to fight a war not of their choosing. When September came, I had seven months before my two years of active were satisfied and I could go back to college. I was over the Navy's petty bullshit, especially since leaving Vietnam. Now there was nothing of consequence needing to be done and the first-class PO was a real asshole. Brennan threw in the towel a couple months earlier and declared himself a homosexual to get discharged. Brennan was very bright and could not cope with the Petty Officers. His frustration was becoming neuroses, and he really needed to leave. During the subsequent investigations, I was questioned about his sexual preferences and habits, but I just claimed ignorance.

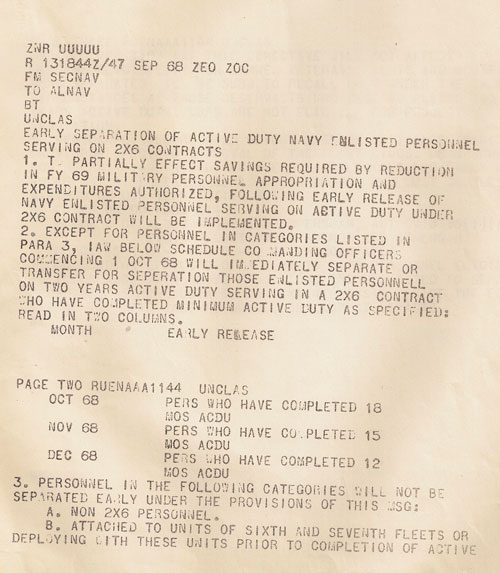

September 13th brought the best unexpected gift I could have asked for. We received a message during my watch from the Secretary of the Navy titled “Early Separation of Active Duty Navy Enlisted Personnel Serving 2x6 Contracts”. Well, that meant me. As I read on, there was a timetable for October release for those who had served 18 months, and progressed to December release for those who had served for 12 months. I just went from seven months left in the Navy to three weeks! What's more, I was to be credited for a full two-years active duty with regard to VA benefits since I was being discharged for the pleasure of the Navy (budget cut). It was the morning of October 8th and my discharge day finally had come. My duffel bag was packed, shoes were polished, and I was ready to be a free man for the first time in 18 months. On the way to breakfast, Latshaw intercepted me and warned me not to go to the mess deck because Jonesy was waiting there for me. Jonesy was our first-class Petty Officer and a real jerk. He never was the same since the morning I made tea instead of coffee in the radio shack coffee urn. He came in with his mug and filled it up the usual way, put in lots of sugar and milk, then took a big drink. We waited with baited-breath across the room for his reaction, and weren't disappointed. He exploded. He knew instinctively I had something to do with it, and it seemed at first he was going to assault me. If the Commanding Officer hadn't shown up just then, he probably would have. This morning Jonesy was going to get even. He hated me for many reasons besides the tea thing and it irked him to have to watch me smile as I walked out of his control and miserable life. One of Jonesy's many peeves with me was the length of my hair, so he was going to take me to the ship's barber one last time before I was discharged. But first, he had to catch me, and my scouts were everywhere. I ended up hiding out in the kitchen area for an hour until Jonesy went looking for me. When I heard the coast was clear, I scurried to the quarterdeck, off the ship, and out to my Peugeot; and never looked back. I drove from San Francisco to Temple City in southern California on October 8th, 1968, wearing my pressed dress blues and carrying my discharge orders. The ribbons on my left chest included the Vietnam Service Medal/Bronze Star, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal, National Defense Service Medal, and Navy Unit Commendation Ribbon. On my right chest was a self-awarded medal which was a bronze peace sign hanging from a red, white, and blue ribbon. All the way home, no one questioned the authenticity of this medal.

|