Amazon (0692645756 gray tones; 1530831903 color) and Kindle (ASIN: B01DUPLUAU).

Many don't think of scientists as adventurers. Some don't think of geologists as scientists (e.g., ask Sheldon Cooper of Big Bang Theory). But rest assured, geologists can be both scientists and adventurers. This fun book chronicles many of Bill Connelly's adventures around the world in his pursuit of geology.

How could he have known of the adventures in store for him when he elected to pursue a degree in geology? His teens had been exciting and a bit wild with his friends Glenn and Gerald, who together drove and hiked all over the western States, generally staying out of trouble. The Navy shipped him to the west Pacific during the Vietnam era and exposed him to military life, travel, foreign cultures, and war. Back in college after the war, he intended to become a marine biologist or zoologist and took numerous courses in those subjects. But after two introductory courses in geology, he was hooked. Perhaps it was the intrigue of geologic time or the magic of physics that compelled him to change to physical science. Having declared a geology major, he never looked back and studied diligently for six more years to earn a B.S. and Ph.D. For his dissertation, he studied subduction complexes in southwestern Alaska where he mapped the coast of the Kodiak Islands from an inflatable boat with Casey and Malcolm. During five field seasons in Alaska as a graduate student, then as Party Chief with AMOCO, he blossomed. How could a job be so stimulating and adventurous? As years ticked away, geology took him to Colorado, Washington, Russia, China, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Canada, Albania, Norway, Japan, Luxemburg, Israel, New Mexico, Venezuela, and Texas. Forty years passed like a speeding train, but with no regrets since the journey continues to be exciting and colorful. As a husband and father, I've told the family many stories of my adventures. While on road trips, hiking, or just sitting around the dinner table, I was reminded of exciting times in distant lands. Bernadine and the daughters enjoyed the stories, so they continued year after year as the girls grew. Now Sage, Serene, and Celeste are married women in their thirties and have their own beautiful families. Celeste was the last of the daughters to marry and her wedding was in 2010. To my surprise, she requested an unusual gift for her wedding: she asked me to write many of these stories for her.

Bill and Celeste Connelly After completing stories about Alaska, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Norway, I decided to step back in time and write about my brother Bobby, my teenage years, my tour in Vietnam, and our years in New Mexico and Venezuela. Stories have taken the form of chapters in a chronologic framework, though they often drift back in time. It's been enjoyable for me to revisit memories of these exciting times and I thank Celeste for inspiring me. Chapter One begins abruptly in the Kodiak Islands where we were constructing a geologic map of the Islands from an inflatable Zodiac. I was a graduate student at the University of California at Santa Cruz and this mapping was part of my dissertation. The reader is provided no background about my disposition, desires, or personality. Since this was originally written for my family, none of this was necessary. For someone who knows nothing of me, here are a few self-descriptions at the time Chapter One begins: academically intense, single and seldom dated, humble, adventurous, enjoyed the wilderness, avoided large groups, athletic (running, bicycling, hiking, surfing, scuba, and swimming), and had a good sense of humor. So there it is; we're off to the Kodiak Islands.

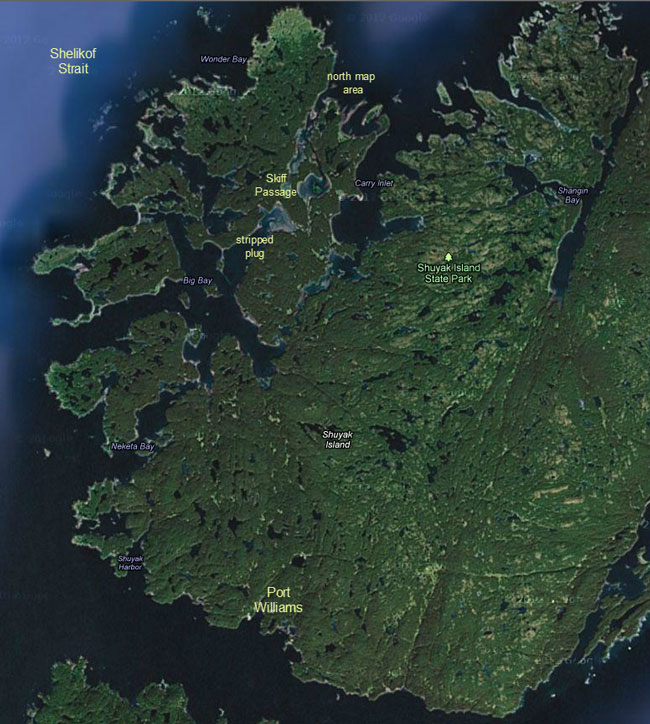

1. Skiff Passage It was late August, 1974, and our second field season in the Kodiak Islands was drawing to an end. We'd nearly finished our geologic mapping of the northwest side of the Islands (Connelly and Moore, 1979) and the weather was growing cool and damp as the Alaskan autumn set in. We'd been systematically working our way north from one fiord to the next in our inflatable Zodiac, living in abandoned trapper's cabins and our tents along the way. We were now staying at a remote cannery called Port Williams in the far north Kodiak Islands and mapping our way around Shuyak Island as weather and rough seas allowed. We enjoyed staying at the cannery since we ate dinner there with the workers most evenings, which commonly included fresh halibut.

Bill Connelly pointing to Kodiak Islands; billboard located in Santa Cruz.

The topographic relief is gentle in the Shuyak region, but the fiords are deep and the vegetation is extremely thick with Sitka Spruce, fern, Dutch Iris, tall grass, and lots of Devil's Club. Most of the Kodiak Islands are relatively barren of trees with thick tundra and occasional Alders. During the Pleistocene ice age, vegetation was pushed off the islands and they were covered by glaciers. Now the spruce are re-vegetating the islands from the north southward at about two feet per year. The spruce-line now is in north Afognak Island so that all of Shuyak is forested with spruce. And under the spruce forest is a plant from hell, which we never before had seen, called Devil's Club. Devil's Club grows to about five feet high with many individual flexible stocks on each plant. At the end of each stock is a large broad leaf, and along the stock are countless inch-long thorns. The thorns are very thin and can penetrate anything except the thick Helly Hansen foul-weather gear. The thorns easily penetrated leather work gloves and jeans. Thus walking cross-country in the Shuyak region was impossible, even in an emergency. The Aleut cure for imbedded thorns in hands or legs was urinating on them, causing them to fester and slip out.

Devil's Club.

Our daily work routine started early with a C-rations meal which the US Geological Survey kindly provided us as part of our National Science Foundation support for this project. The C-rations were left over from the Vietnam war, which ended in 1969, so they weren't exactly fresh. Most of the time I worked with Casey Moore, but sometimes with Malcolm Hill. Only occasionally were the three of us all there at the same time. As we were finishing the 1974 field season at Port Williams, the three of us spent a rare three weeks together. We generally split up and I would map a section of sea cliff for most of the day while they worked another section of the coast. At the end of the day they would find me and pick me up in the Zodiac and we would head back to the cannery for dinner. Then we would organize our notes, pack rocks, post maps, and get rested for the next day. During the months we worked along the Kodiak coast, we became very familiar with the sea. When we first arrived in Alaska we feared the giant Kodiak bears and always carried magnum pistols and rifles. As time passed, we realized our fears were misplaced and it really was the sea that was to be most feared. We still carried our guns and had our share of run-ins with the bears, but we came much closer to our maker with the ocean than with wildlife. We paid close attention to the ocean to learn her ways. The tides along the Shelikof Strait are extreme and exceed 20 feet during full moons and new moons. When tides fluctuated this high, driftwood was set afloat so travel by Zodiac was more hazardous. The coasts all are rocky and reefs are everywhere. One of us would drive the skiff while the other kept his eyes peeled for hidden reefs. On occasion, the tail shaft of the outboard would strike a rock while speeding along and the outboard would fly forward. We quickly learned to keep our knees out of the way less we shatter them.

Our skiff was named SuperHot. Sometimes strong winds would funnel down small canyons to the coast. As we sped by the canyon's mouth in the skiff, the wind would try to lift the bow and flip it. These surprise winds are called “willow-waz”. Hazards for skiffs were countless and I'll not write now about the Orcas or Sea Lions or Aleut boys with nails. When you parked the skiff for a time to map a section of sea cliff by foot, you needed to be sure to leave it somewhere it would not float away during your absence. Yes, the tides; always the tides. We carried tide tables in our packs and we always double-checked where the tide was when we left the skiff, and where it was likely to be when we expected to return. We had to remove the kicker (outboard) and gas cans and carry them to higher ground. Then we rigged up a rope across the stern with some foam rubber we found on the beach to go over my shoulders. I would carry the stern with the rope, and Casey would carry the bow. Often this was major work since much of the coast was lined with cobbles covered with seaweed and slime. Real ankle twisters. Obviously we didn't want to carry the heavy skiff any farther than needed, but we wanted to be sure it was far enough up that it would still be there when we returned. We learned about the different kinds of kelp that grew along the coast, and what each one's tidal range was. This was valuable knowledge. The amber kelp grows as high as +17’ tide. If the high tide for the day was +14’, we could leave the skiff a couple feet below the amber kelp line. The season was coming to an end and we were hoping to map the far northern shoreline of Shuyak Island, but we couldn't access it due to the long skiff ride in the rough seas of Shelikof Straits. Then came my brilliant idea of a shortcut through the interior of the Island to avoid the rough seas. There is a small tidal channel that runs northward from the head of a deep fiord on southwest Shuyak Island to a large lagoon in the center of the island, to a tidal channel accessing the north shore of the Island. When mapping this area one day, it seemed to me it would be possible to navigate the tidal channel northward to the lagoon if the tide were +18’ or higher (based on the amber kelp line). If we timed it right, the tidal currents would be flowing northward with us on our way into the lagoon as it filled. We could then leave the lagoon on the north side as the tide started to drop, again enjoying traveling with the current. Casey, Malcolm, and I would be making the trip and we would spend three nights on the north side of the Island. The Zodiac would be heavy with people, gas, and equipment, and it would be difficult to get the skiff up and keep it up on a plane. The tidal channel was shallow with tight meanders, so it was important to keep it on a plane or we would hit rocks with the kicker.

West Shuyak Island with Skiff Passage and central lagoon. Port Williams on south end of map; Shelikof Strait on west. The plan looked solid and Casey and Malcolm agreed to give it a try. We waited seven days for the next super-high tide and set off on our adventure. It was more difficult than we anticipated keeping the Zodiac on a plane since there were so many tree limbs hanging close to the water. We were constantly ducking, while at the same time dodging rocks. Casey drove the skiff while I hung onto the bow line like a bucking bronco, spotting rocks by pointing to them as we sped along at 20 mph, constantly ducking limbs. It was invigorating and Malcolm just sat back and laughed at us. We reached the central lagoon and everyone had a sigh of relief and a sandwich. We kept going though since we needed to exit the lagoon on the north as the tide dropped. The channel on the north was mild compared to the southern entrance and we arrived safely on the far north shores of Shuyak Island where we mapped for the next two days. I drove the skiff during our return through “skiff passage”. The trip was uneventful since we then knew what to expect. Our load was lighter now since we used much of the gas and ate the food. We collected rocks along the way, but there was a net loss of weight. After traversing the lagoon and tidal channel and arriving back into the fiord, the spark plug fouled. The weather was pleasant and the water was flat-calm, so I just killed the kicker and pulled the cover and went about replacing the plug as we floated in the bay. With two-cycle engines, plugs fouled routinely and we always carried tools and replacements. While I was removing the old plug, Casey and Malcolm were chatting and taking pictures and eating snacks. I put the new plug in and tightened it down with the plug wrench. It seemed to take more tightening than usual, but I kept at it. Then I realized …. Thoughts raced through my mind, but no solutions. I thought about walking back to Port Williams, but remembered the deeply indented shoreline and the dense spruce forest and Devils Club. Besides, it was 20 miles away as the crow flew, and 50 miles hiking. This was a very remote area and we hadn't seen a fisherman for weeks. No trappers or cabins; nothing. No radio. Hummm, I guess I should tell Casey and Malcolm and see if they have any thoughts.

Sitka Spruce, Shuyak Island. I politely broke into their discussion about ultramafics, telling them our situation just took a turn for the worse. They were convinced I was kidding. When I said I just stripped the head while screwing in the new spark plug, I saw a dramatic change in their composure. Casey was definitely pissed; Malcolm was digesting the situation. Casey already put it together in his mind and realized we were hosed. We paddled the skiff to shore and unloaded some stuff, and thought. We spent a lot of time thinking, but all were dead ends. We were hosed. We ate our lunch, thought some more, kicked around new ideas, and got depressed. Casey decided to have a hands-on with the kicker, but quickly came away with the same conclusion: the head is stripped. After lunch as I was cleaning up our C-rations, an epiphany came to me. Each C-ration includes a couple cans of food, like pork-and-beans and peaches, some crackers, peanut butter and jam, matches, a tiny can opener, and a pack of four cigarettes. None of us smoked so we always threw away the cigarettes. But I got to wondering if the aluminum foil lining for the cigarette package could be an adequate spacer to seal the plug into the stripped head. I took a piece of the foil to the kicker and carefully wrapped it around the threads of the plug in a counter-clockwise direction and screwed it in by hand; and it seemed snug. I put the plug wrench to it and gave it the slightest turn, and it continued to hold, so far. Could it possibly remain seated for the four-hour skiff ride back to Port Williams? We hadn't come up with any other solutions, so I told Casey and Malcolm what I'd done and they wanted to give it a try. We stripped the skiff of everything non-essential and stashed the stuff in the forest to retrieve another day, and climbed in. I started the kicker and it seemed to run fine. We 'putted' out of the fiord and around the point and out into the Shelikof. In the end, it took us four hours to get back to the cannery, and the foil held.

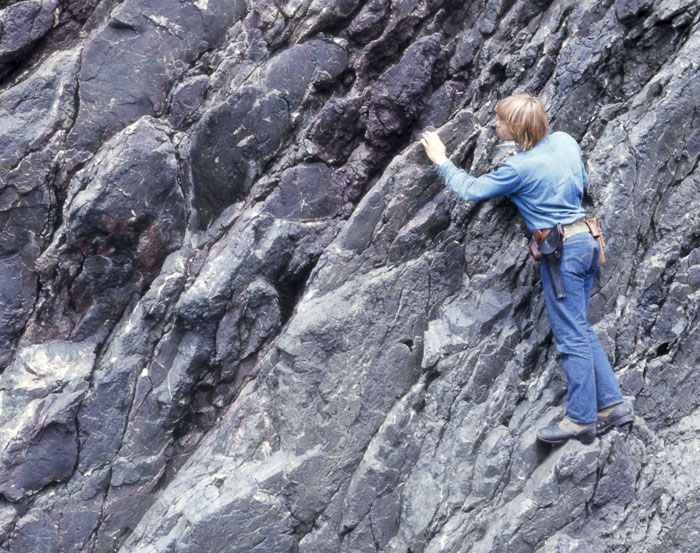

Bill Connelly working on Uyak Complex pillow basalt.

Go to Chapters 2, 3, & 4 |